Table of Contents

The Washington Post’s Jonathan Capehart said he invited Jonathan Metzl, author of Dying of Whiteness: How the politics of racial resentment is killing America’s heartland, back on his Cape Up podcast this month “because the novel coronavirus is amplifying his argument.”

Metzl, director of Vanderbilt University’s Center for Medicine, Health, and Society, told Capehart that his book, published last year, “was a kind of a warning of the lengths to which white working-class voters could either have underlying racism or be manipulated to vote in support of wealthy donors and corporations, but against their own lifespans. And it’s just been on steroids since this pandemic started.”

Almost all of those gun-toting demonstrators who’ve gathered at state capitols to protest stay-at-home and lockdown orders are white. Some of them, like the Michigan protestors, brandished Confederate flags and Trump 2020 signs. The president praised them as “very good people.” (Like those in Michigan, many of the Kentucky capitol protestors were heavily armed and waved Confederate flags.)

“Racism is so deeply ingrained in the psyche of society that it is literally making people crazy,” said Brian Clardy, a Murray State University historian. “It’s scary.”

Racism is so deeply ingrained in the psyche of society that it is literally making people crazy. It's scary. — Brian Clardy, a Murray State historianClick To TweetSo is Metzl’s book. He writes that racism isn’t just immoral, it’s suicidal.

The author spent eight years talking to less-than-well-heeled whites in Republican Red states Kansas, Missouri, and Tennessee. He met “many” who hadn’t bought into what Clardy called craziness. Yet just as often, Metzl found others whose racism led them to elect governors and state lawmakers who pushed legislation “that directly harmed their own health and well-being, or the health and well-being of their own families.”

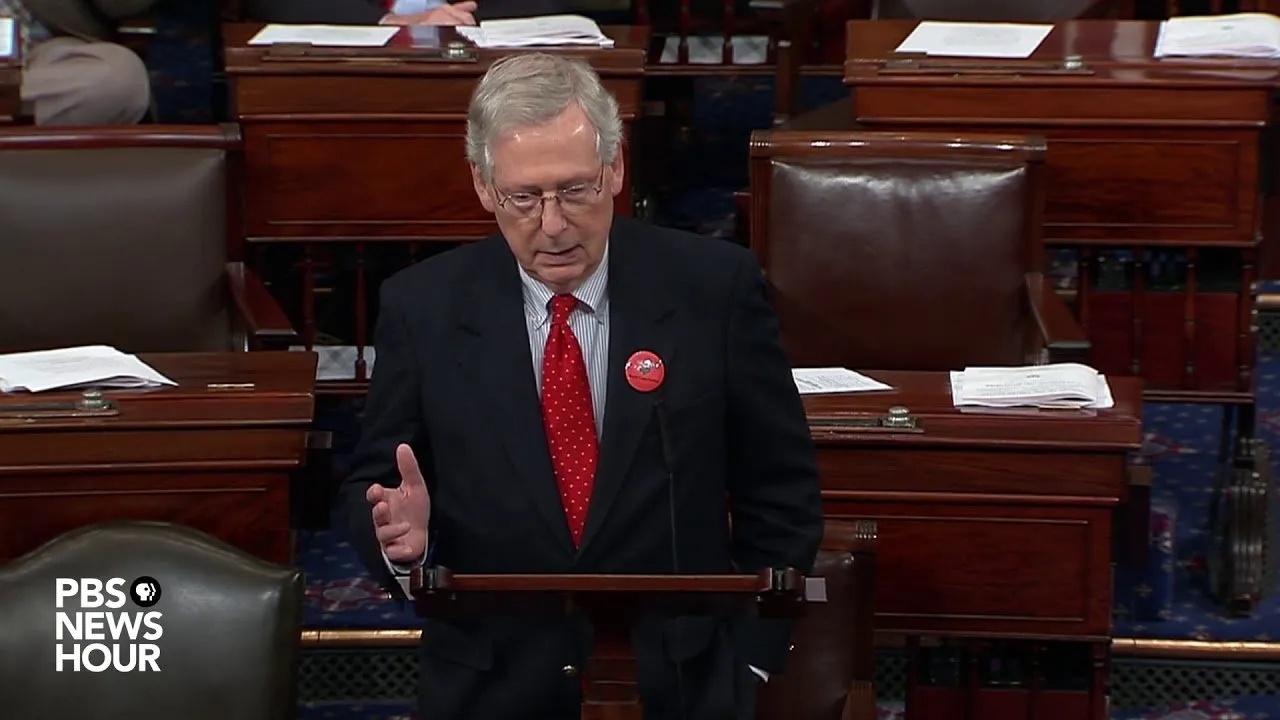

He warned that “as these policy agendas spread from Southern and midwestern legislatures into the halls of Congress and the White House, ever more Americans are then, literally, dying of whiteness.”

Metzl cited Trevor (not his real name), a poor, middle-aged, uninsured white Tennessean who slowly died of treatable liver disease. “Ain’t no way I would ever support Obamacare or sign up for it,” he confided to the author. “I would rather die.”

Metzl asked Trevor why. “We don’t need any more government in our lives,” he replied. “And in any case, no way I want my tax dollars paying for Mexicans or welfare queens.”

Metzl concluded that Trevor’s death “resulted also from the toxic effects of dogma … aligned with beliefs about a racial hierarchy that overtly and implicitly aimed to keep white Americans hovering above Mexicans, welfare queens, and other nonwhite others.” Metzl wrote that “even on death’s doorstep, Trevor wasn’t angry. In fact, he staunchly supported the stance promoted by his elected officials.” (Tennessee’s Republican-majority legislature “repeatedly blocked Obama-era health reforms,” Metzl pointed out.)

When he was Kentucky’s governor, Steve Beshear — a moderate Democrat and the father of current Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear, also a moderate — started Kynect, one of the most successful state exchanges under the ACA. He also expanded Medicaid.

In 2015, hard-right, Tea Party-tilting Republican Matt Bevin, who became a Trump acolyte before Andy Beshear beat him last November, was elected governor after promising to dismantle Kynect and roll back Medicaid.

If Metzl decides to write a sequel to Dying of Whiteness, he might consider visiting the Bluegrass State. “Kentucky counties with highest Medicaid rates backed Matt Bevin, who plans to cut Medicaid,” said a headline in the Lexington Herald-Leader shortly after Bevin won.

“Trump did not invent insecure whiteness,” Metzl wrote in the Washington Post last year. “He is only a skilled manipulator of the fears at its heart.”

Indeed, campaigning in Tennessee a half-century ago, President Lyndon Johnson, a Texan, declared, “If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.”

If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you. — Lyndon JohnsonClick To TweetThe New York Times’ Charles Blow resurrected that quote in a 2018 column. “Trump’s supporters are saying to us, screaming to us, that although he may be the ‘lowest white man,’ he is still better than Barack Obama, the ‘best colored man,'” Blow wrote.

Trevor’s story saddened but didn’t surprise Clardy. “There were many people who refused to participate in the [ACA] and wanted the system gone just because if was offered by a black president. How scary is that?

“Now you have a situation where a lethal virus is killing hundreds of thousands of people around the world — and we’ve gone over 100,000 deaths in this country — and people are carrying guns and trying to force state governments to reopen. People are not wearing masks, not social distancing and intimidating politicians, knowing that when states reopen, people are going to die.

“Endangering themselves and their families just to make a political point is insanity, pure insanity.”

–30–