Table of Contents

Editor’s note: The following is a story from 2020 that we are reposting now, due to this year being the mid-terms. Other than the opening grafs, it is still quite timely.

With the 2020 campaign season upon us, “dark money” is again in the news.

Maine’s Republican Sen. Susan Collins has decried what she contends is a “dark money” campaign against her. Montana’s Gov. Steve Bullock has made opposition to dark money a centerpiece of his Democratic presidential campaign.

But what exactly is “dark money,” and why is it considered a problem?

As a law professor who studies campaign finance, I’d like to answer those questions and explain how improved disclosure laws could shed some light on dark money.

1. What is ‘dark money’?

Election campaigns run on money.

Money pays for salaries, travel – and especially advertising. Candidates who are not personally wealthy depend on contributions to cover those costs, or on supportive spending by political parties and other political groups. Since the Watergate scandal in the 1970s, federal laws have imposed limits on political contributions and required that candidates disclose to the Federal Election Commission the sources of most donations used in federal campaigns. Most states have similar laws governing their elections.

In the first several decades after the enactment of disclosure requirements, most federal campaign spending was disclosed. But changing campaign practices, particularly the growing role of outside groups that are neither candidate committees nor political parties, has enabled some large donors to hide more of their giving. Starting in 2010, campaign finance observers at the Sunlight Foundation began to refer to some of these unregulated funds as “dark money.” The term was popularized by a best-selling 2016 book by Jane Mayer.

“Dark money” refers to campaign money whose sources are not disclosed. An expenditure – for example, for a television ad criticizing an opponent – will often be publicly reported to the FEC but not the identities of the people, firms or organizations that pay for it.

2. Is ‘dark money’ a problem?

Many scholars think it is.

A lack of disclosure makes it harder for journalists, regulators and opponents to detect violations of campaign finance law, such as illegal contributions from foreign donors or government contractors and contributions over the legal limit.

It also hides legal contributions from disreputable sources like Harvey Weinstein or Bernie Madoff.

That’s not all. The lack of disclosure also denies voters valuable information. As the U.S. Supreme Court observed in Buckley v. Valeo, the landmark 1976 decision that upheld federal campaign disclosure laws, identifying a candidate’s financial backers “alert(s) the voter to the interests to which the candidate is most likely to be responsive.” This is particularly significant in primaries when all the candidates are in the same party, and voters can’t rely on party labels to decide whom to vote for.

In the current Democratic presidential race, for example, disclosure allows voters to verify candidates’ claims about donors, revealing that former Vice President Joe Biden has courted lobbyists, Sen. Elizabeth Warren gets nearly 30% of her money from large individual donors, or that some Silicon Valley donors are supporting South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg. Knowing these details helps voters understand what interests a candidate may favor if elected.

To be sure, disclosure has its critics. Last summer’s kerfuffle over Rep. Joaquin Castro’s tweeting the names and employers of large donors to President Trump – all of which had been disclosed as required by law – underscores the concern of some people that disclosure is an invasion of donors’ privacy.

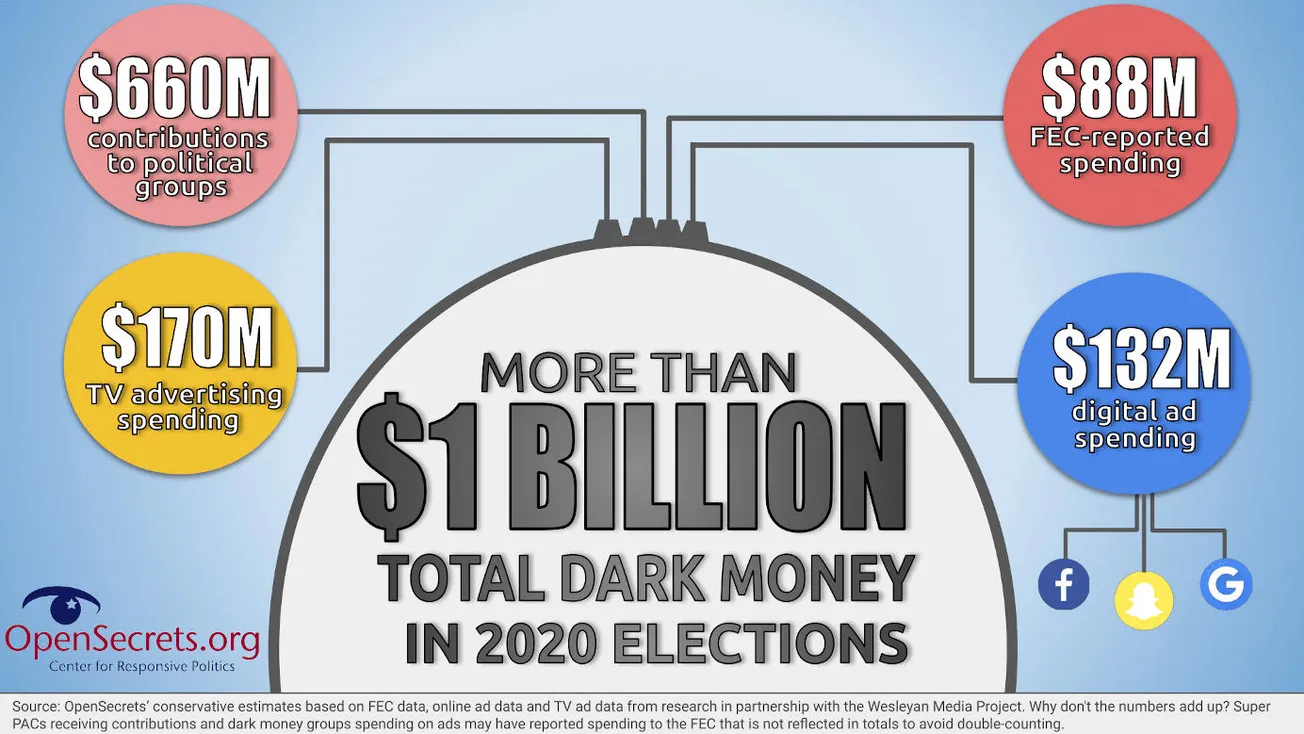

3. How much dark money is out there?

Due to its very “darkness,” it is hard to know just how much dark money is being spent, but there is reason to believe the number is large and growing.

Remember: Some dark money spending is reported to the Federal Election Commission without disclosing donors and some dark money spending isn’t reported at all. The campaign finance watchdog Center for Responsive Politics found that dark money groups reported spending US$181 million in the 2016 federal elections. Dark money accounted for nearly a fifth of all spending by groups other than candidates and parties in the last decade.

But these figures account only for spending reported to the FEC and likely represent only “the tip of the iceberg,” according to the center. As long as campaign spending is not subject to disclosure the total amount of dark money is unknowable.

4. Why is it possible to hide donations?

Dark money grows out of gaps in our campaign finance law.

Federal election law most clearly addresses reporting and disclosure by candidates, political parties and political committees that exist primarily to support candidates and parties. But other organizations also participate in elections. These include business groups and trade associations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, membership organizations like the National Rifle Association or the League of Conservation Voters, labor unions, and ideological groups like Americans for Prosperity or Patriot Majority USA.

These groups do not have to report their donors because they claim to work on issues and not on behalf of specific candidates.

There are some exceptions. If the group spends a significant amount on a campaign ad, it will have to report the spending and any donors who specifically helped buy it. But the law covers only some campaign ads. The Buckley decision held that only ads literally calling for the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate – what the law calls “express advocacy” – are campaign ads subject to disclosure.

That means that organizations can sharply attack or warmly praise a candidate in ads but avoid disclosing donors by stopping short of telling people how to vote. These “issue ads” are not subject to disclosure.

In 2002, Congress passed the McCain-Feingold law, which extended disclosure to include broadcast ads that mention a candidate 30 days before a primary and 60 days before a general election, but similar ads aired earlier in the campaign season are not covered.

Following the money is made more difficult because many nominally non-political organizations fund campaign ads indirectly. They do this by donating to another group which buys the ad. Sometimes, even that second group transfers the money to a third organization before the ad purchase it made.

This “daisy chain” or “nesting Russian doll” practice is an end run around disclosure.

Even though the organization that actually does the spending must disclose its large donors to the Federal Election Commission, these reports simply list a contribution from the next link in the chain – which tells the voters nothing about who actually paid.

5. What can be done?

The problem of “dark money,” while serious, can be addressed with legislative fixes.

First, all organizations – including corporations, labor unions and non-profits engaged in election-related spending – could be required to disclose large donors whose funds are used for campaign ads. The Citizens United decision struck down limits on corporate spending, but it also sustained the law requiring corporations to disclose their spending.

Second, when the disclosed donations are from an organization further down the daisy chain, the disclosure could include the major donors to that organization. Several states, such as New Jersey and Colorado, have recently passed laws requiring that information.

The U.S. House of Representatives this spring passed similar legislation addressing large dark money donors and spenders in federal elections, although Republicans in the Senate seem unlikely to take it up.

To be sure, some constitutional issues remain – particularly the definition of what constitutes an election-related ad. But because disclosure does not limit or bar the use of campaign money and increases voter information, the court has regularly found disclosure to be consistent with the First Amendment.

In other words, unlike many other issues in campaign finance reform, the obstacle to improved disclosure is political, not constitutional.

--30--

Written by Richard Briffault, Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation, Columbia University. Cross-posted from The Conversation.