Table of Contents

Co-authored by Kim Banta and Kimberly Kennedy

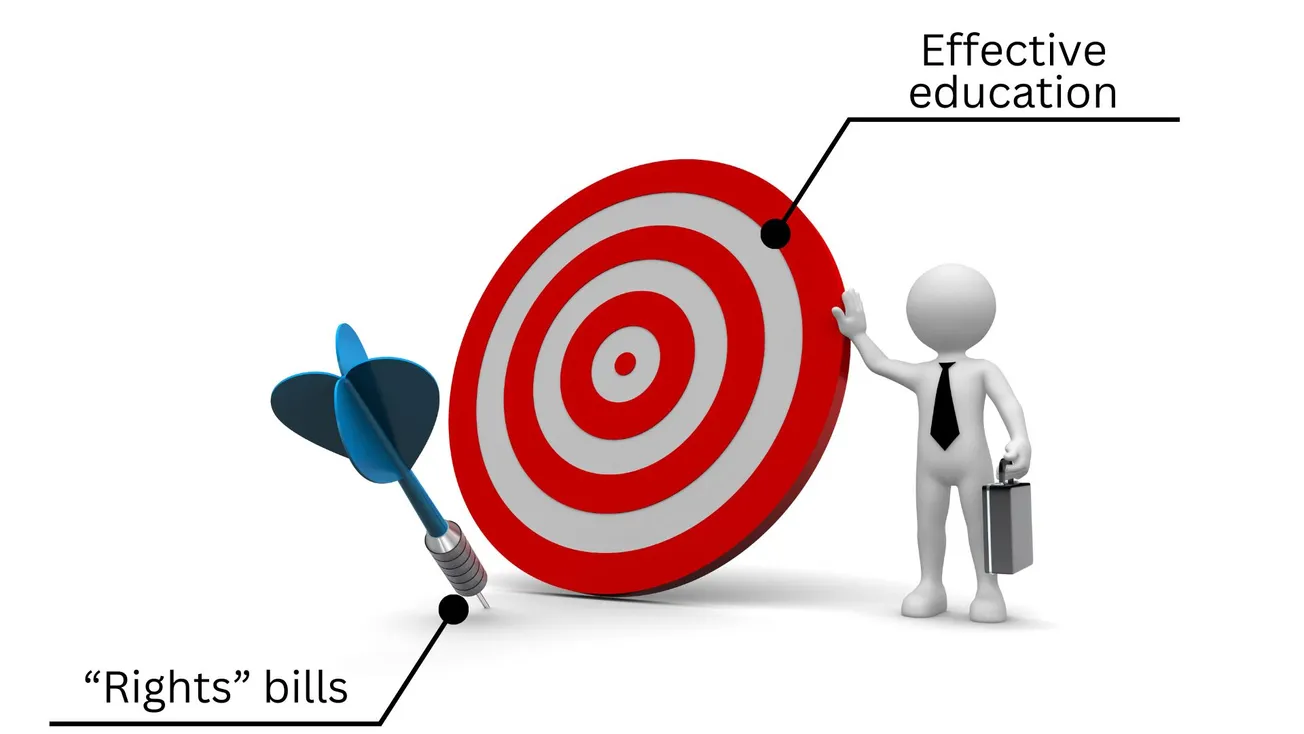

The two of us, a Democrat and Republican, have come together as former educators to talk about the “Parental Rights in Education” movement sweeping not only the nation but also the Kentucky legislature, with five bills gaining traction: House Bills 175, 175, and 177, and Senate Bills 102 and 150.

These bills demonstrate “solutions in search of problems” that largely don’t exist. They’re symptoms of a false narrative that unnecessarily creates an adversarial relationship between parents and teachers and doesn’t represent the views of the majority of either group, who see their relationship as a partnership.

Common provisions in Parental Rights legislation include:

- Requiring teacher instructional transparency and age appropriateness,

- Banning books and discussions about objectionable content and allowing parents to opt-out their child,

- Allowing teachers to use religious-liberty objections and disrespect LGBTQ+ students,

- Creating avenues, including legal, for parent grievances.

These provisions send the message that parents can’t trust educators’ judgment, and that teachers don’t have the qualifications nor expertise to educate our kids, despite Kentucky’s requirement for an advanced degree plus extensive continuing education for all teachers.

Banning topics unnecessarily muzzles teachers from engaging in discussions and answering student questions. We can’t assume that kids — even young ones — don’t notice their environment and thus have questions, like why their friend Joey has two daddies, or why the movie they glimpsed at their friend’s house showed a black man beaten with whips. If, for example, we don’t teach about sexual orientation — at an age appropriate level — we don’t equip students to deal with the LGBTQ+ people they will encounter. If we don’t teach our history of racial injustice, we give an incomplete historical context to the racial pressures our society is experiencing today. Allowing students to opt-out would give them an incomplete education. Parents always have the opportunity to discuss a topic with their child and impart their own values.

As for controversial books, bear in mind that books are reviewed by library/media specialists, in concert with administrators, before placement in the library and classrooms, using national standards for developmental appropriateness.

Learning about controversial topics is not harmful. Teachers are trained to expose students to multiple sides of issues (and manage students’ feelings) — not indoctrinate them to one point of view — so that students learn to think critically, to make decisions for themselves. Moreover, learning about cultural and subcultural differences creates more understanding and thus respect for differences, minimizing the us-against-them mentality, and ultimately creating a more peaceful society. Isn’t that a good thing?

Are there some teachers who miss the mark? Absolutely, and there are means to address this. But most teachers look for an avenue to reach each and every student. They work to gain students’ trust so each student will come to their classroom with an open mind, willing to learn. Using students’ preferred nicknames and pronouns is a simple way to build mutual respect, trust, and cooperation. Treating a student as “less than” because they are exhibiting something that makes the teacher uncomfortable would disrupt the pathway to learning.

As for transparency, parents already have access to all curriculum. And with modern technology, there are more ways than ever for teachers to keep parents informed (as well as procedures for parents to dispute content), including teacher websites and online posting boards which detail assignments, syllabi, grades, attendance, messages, etc. To require more would unnecessarily burden educators and discourage spontaneity. Besides, learning isn’t just formal lesson plans with objectives; it’s often informal, like when a teacher calms a dispute with conflict resolution, or models acceptance of everyone.

Furthermore, allowing state-sanctioned curriculum omissions or student discrimination, as through the religious objections of teachers, invalidates the social contract between citizens and public schools: that they will provide a comprehensive education to every child. Forcing teachers to “out” students who present as LGBTQ+ inserts teachers into private family matters and assumes that all parents are supportive and accepting; instead, outing students endangers those whose parents/guardians may be dangerously punitive in their response. Teachers are already obligated to contact parents about things which interfere with the learning process, like behavior, health, or academic concerns.

We have seen the painful struggle of students who were perceived as different, and we have made extra efforts to be more accepting so that their school day is less miserable. Schools should be safe, happy places — not judgment zones where marginalized kids feel unsafe — or the consequences could be tragic.

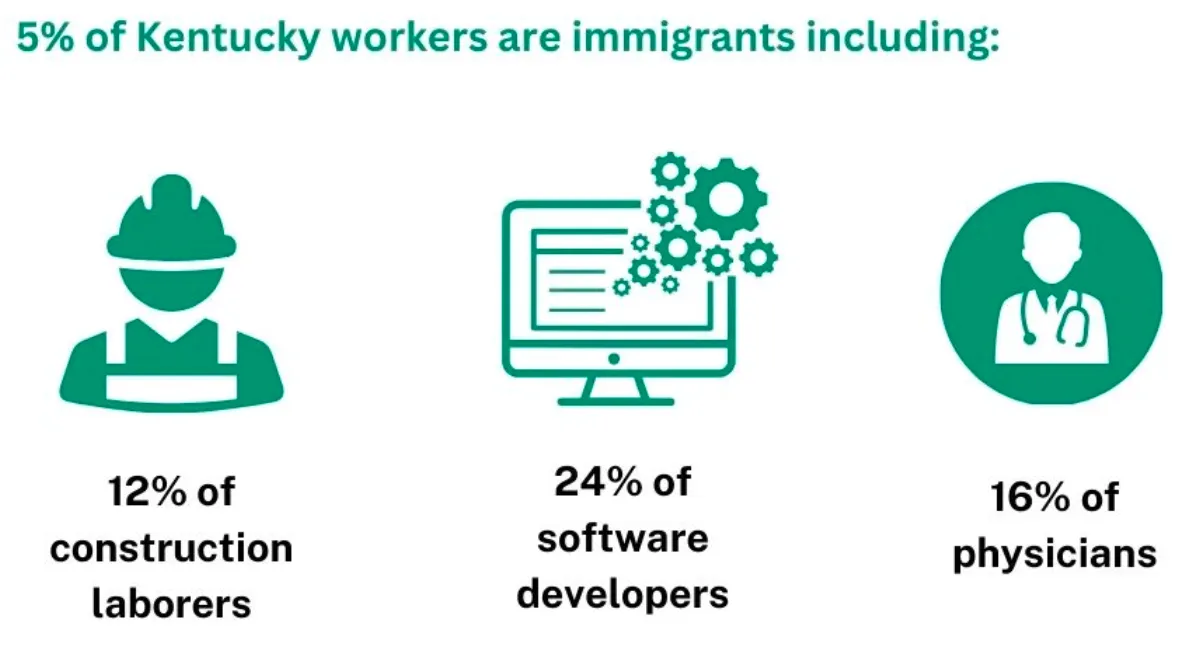

It’s time to spray a fire hose on the hostile teacher rhetoric and consider the broader consequences, including teachers leaving the profession (adding to the teacher shortage), college students averse to entering the profession, and companies doing business elsewhere. Let your legislator know you’d like them to focus on more pressing issues, like homelessness, addiction, family-care leave, and infant and maternal mortality, among other things.

Let’s trust and respect teachers, allowing them to do the job they were trained to do — in partnership with parents — keeping in mind education’s broader mission: to prepare all students for a diverse 21st-century society.

--30--