I don’t know how many times in the last three years that I’ve noticed this skinny tree on Interstate 69 — the old Purchase Parkway — just east of the Mayfield airport.

The tree is maybe 10 feet off the inside eastbound lane. It looks like any other tree except for a small sheet of dull, light-colored metal that’s bent around the trunk and tangled in some branches. It might be a gutter from a house or other building.

Though I don’t know what the metal is, I know how it got there. I often wonder if other travelers know, or even notice it.

The tree is a reminder, if obscure, of the deadliest and most destructive night in the history of Mayfield, my hometown.

Three years ago tonight, one of the most powerful tornado outbreaks in Kentucky history — aptly nicknamed “The Beast” — struck western Kentucky from the southwest. The massive storm twisted a diagonal swath of death and devastation across Graves County and Mayfield, its county seat, before continuing eastward, unabated.

The system killed two dozen people in the city and county before victimizing Princeton, Dawson Springs, Bremen, and other western Kentucky communities. All told, the outbreak claimed 80 lives statewide.

In 2000, Melinda and I retired from Mayfield to Arlington, her hometown, 23 miles west of Mayfield. The tornado struck on Dec. 10, 2021, a Friday night. We stayed home Saturday, not wishing to join the crowd of ghouls and gawkers who inevitably show up at disasters and get in the way of first responders.

We came to Mayfield on Sunday. Melinda attended a joint First Christian-First Presbyterian communion service. The Beast destroyed both houses of worship and several other churches in town.

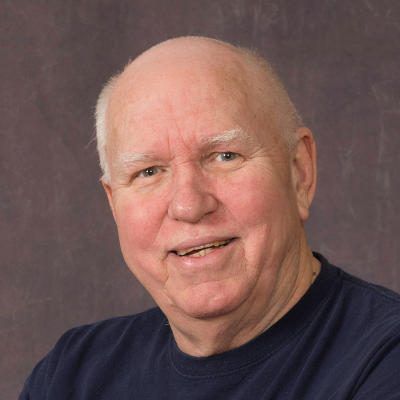

I grew up in First Presbyterian, and Melinda is an active member. That day, I took the first of many photos and wrote the first of many stories for Louisville-based Forward Kentucky.

I have never been in war, but I imagined Mayfield looked like a war-torn town.

For my 75th birthday Saturday, Melinda bought me an old copy of Paducah-born writer Irvin S. Cobb’s Paths of Glory: Impressions of War Written At and Near the Front. Before he became a famous novelist and humorist, Cobb was a journalist and one of the country’s most celebrated World War I correspondents.

Paths of Glory is his first-hand account of the fighting on the Western Front in 1914-1915, the first two years of the global conflict that was supposed to end war and make the world safe for democracy – but failed on both counts.

Cobb’s impressions of Belgian and French towns laid waste in savage fighting seemed remarkably similar to mine of Mayfield after the tornado.

He and other correspondents arrived in La Buissière, Belgium, in August, 1914, just 48 hours after the Germans had driven French forces out of the town in heavy fighting. The tornado had departed 48 hours before we were in Mayfield.

“This town, if it was like every other Belgian town, must have been as clean as clean as could be,” he wrote. “….But the war had come to La Buissière and turned it upside down.”

The tornado did likewise in Mayfield. The twister destroyed dozens of homes and businesses in town, flattened a huge water tower and felled hundreds of trees. It tossed vehicles around like toys.

The tornado gutted the downtown, damaging or destroying the old Hall Hotel, First National Bank, city hall, the police and fire stations, the 1880s-vintage Graves County courthouse, stores, the Mayfield Messenger office, Carr’s Barn barbecue cafe, and more.

Besides First Presbyterian and First Christian, the tornado wrecked First Methodist, St. James AME, and Fairview Baptist churches. First Baptist was hard hit, but still stood.

Cobb characterized La Buissière as “as an indescribable jumble of wreckage.” Mayfield was too.

“A war wastes towns, it seems even more visibly than it wastes nations,” he wrote. Mayfield residents who survived The Beast on Dec. 10, 2021, might agree.

Amidst the tornado’s dusty rubble of broken bricks, shattered glass, splintered wood, twisted metal, broken utility poles, and downed power lines, I spotted a little yellow, stuffed Tweety Bird lying forlorn in a gutter on West Broadway. The orphan was grimy but intact. I picked it up, dusted it off, and stuck it in my pocket.

My thoughts turned to Tweety when I turned to page 79 in Cobb’s book: “Just as we turned back to return to the town I saw a child’s stuffed cloth doll — rag dolls I think they call them in the States — lying flat in the road; and a wagon wheel or a cannon wheel had passed over the head, squashing it flat.

“I am not striving for effect when I tell of this trifle. When you write of such things as a battlefield you do not need to strive for effect. The effects are all there, ready-made, waiting to be set down.” The same is true for a town that is a victim of a tornado.

I have no idea how Tweety ended up in that grimy gutter. Cobb was clueless about the doll.

“Nor do I know how a child’s doll came to be in that harried, uptorn place,” he wrote. “I only know it was there, and being there seemed to me to sum up the fate of little Belgium in this great war. If I had been seeking a visible symbol of Belgium’s case I do not believe I could have found a more fitting one anywhere.”

Like the tree on I-69, Tweety is another visible symbol of the tornado that forever changed the community where I was born, reared, and lived most of my life. Throughout Mayfield’s 200 or so year history, people marked time spans by before or after the Civil War, World War I, the Great Depression, World War II and even the ice storm of 2009. Henceforth, it will be before or after The Beast.

Cobb evidently left the doll in the road. Tweety is in our house in a plastic case, along with my other tornado souvenirs: a grungy, but determinedly cheery, stuffed snowman, a torn “Merry Christmas” banner, and a little plastic cow with one ear missing.

Anyway, I will think of Dec. 10, 2021 tonight, about the weirdly warm weather, and about wearing a tee-shirt to supper at Nanny Jo’s restaurant in Arlington with Melinda, her brother, and his wife.

I will remember that it was barely raining when we drove home, when we settled in to watch a movie on TV, and when Melinda’s iPhone pinged with the first of many text messages: “A tornado has hit Mayfield.”

--30--