Andrew McNeill went to the Kentucky legislature last month with a straightforward ask: scrutinize the state’s habit of awarding costly road construction contracts to the only firm that bid for the job.

McNeill, a deputy budget director under former Republican Gov. Matt Bevin, told the legislature’s interim joint committee on transportation that he analyzed the state’s data and found single-bid contracts, specifically, were driving up the cost of construction projects in Kentucky.

If the legislators ordered an audit they could get to the bottom of why, said McNeill, a fellow at the Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions. But the lawmakers didn’t bite.

They instead jumped to defend the contractors, criticize McNeill’s analysis of the state’s data and ultimately showed little interest in boosting oversight of a lucrative industry with a history of corruption allegations and shrinking competition.

State officials awarded nearly 2,300 road work contracts between 2018 and October 2021, according to a Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting review of state data. A third of those were single-bid contracts, in which the company awarded the contract was the only bidder. (One month of 2019’s bidding data was missing from records provided by the state.)

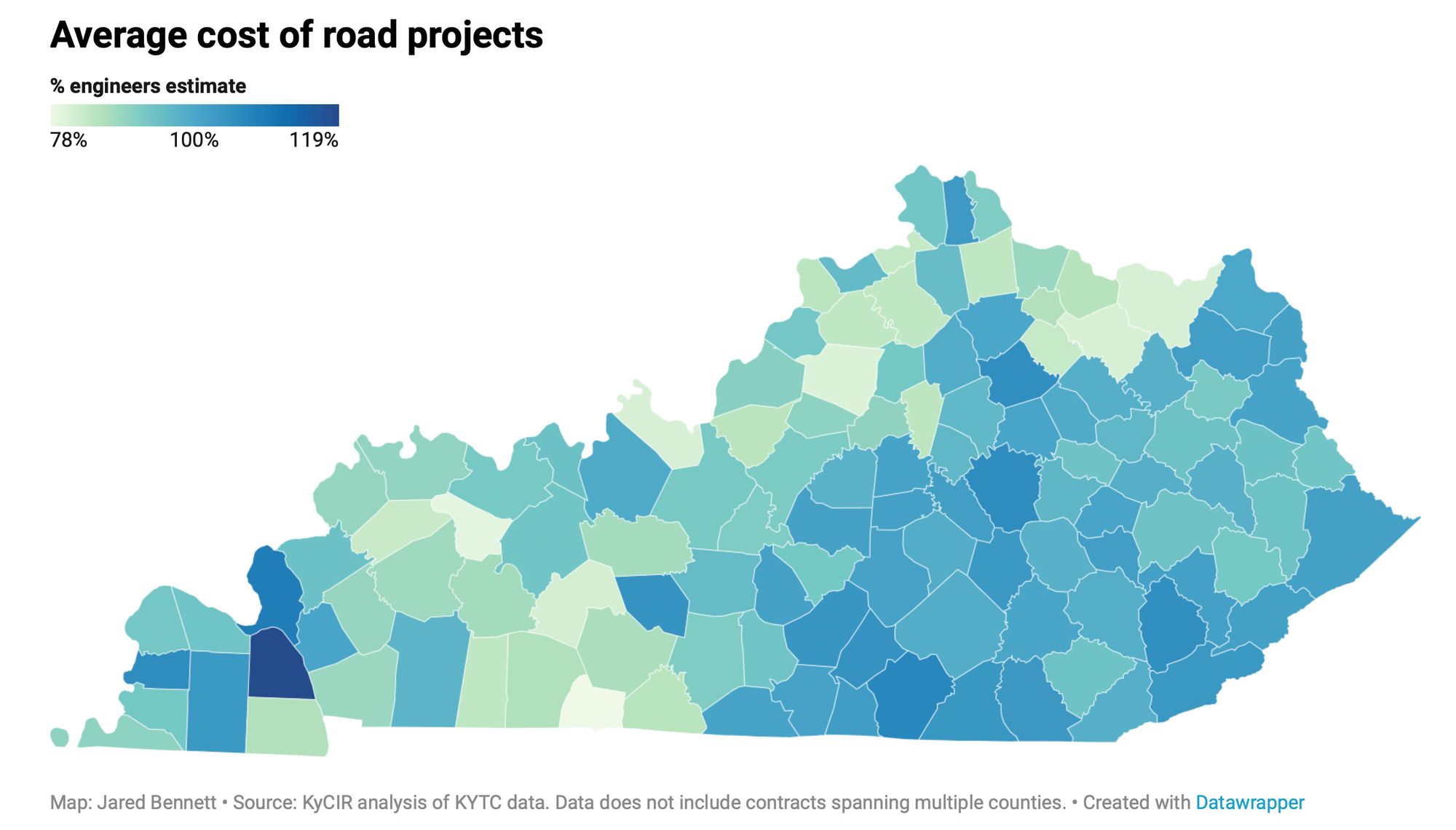

Nearly 60% of single-bid contracts were awarded at costs above engineer estimates, totaling $9.6 million more than state projections, according to KyCIR’s review.

In contrast, the projects in which multiple companies submitted a bid were awarded at, collectively, nearly $248 million below state estimates — a 7% savings.

The same day McNeill spoke to Kentucky lawmakers, President Joe Biden signed a historic infrastructure spending law, setting the stage for a significant boost in federal funds going towards Kentucky projects.

Some of that money will likely flow through the state’s transportation cabinet, which already manages a massive segment of the Kentucky economy. More than 1,300 active contracts across the state are worth $7.5 billion.

The transportation cabinet is exempt by law from following the state’s procurement code, instead following a bidding system experts say allows a handful of large companies to avoid serious competition for jobs.

As a result, more than $2 billion in current work is controlled by a dozen companies — who often are the sole bidder on the contracts they’re awarded.

A spokesperson for the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet declined to make officials available for an interview. The cabinet has not yet responded to questions emailed by KyCIR.

Fewer bidders, higher costs

When it comes to road construction and maintenance, the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet has few safeguards to discourage awarding single-bid contracts.

Most winning bids come in under the state’s engineers estimate, and competitive bids drive costs down further. But Kentucky’s rules don’t prevent the state from accepting a lone bid, regardless of the project’s size.

That has led to higher costs for taxpayers: The KyCIR analysis found that more than half of the 782 single-bid contracts were awarded for a price above the state estimate, whereas 85% of multiple-bid contracts were below state estimates.

And a 2015 survey by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials found that Kentucky had the third-highest percentage of single-bid contracts for asphalt work in the country. The survey also found that while construction costs were steady or dropping in a majority of states, prices were increasing in Kentucky by an average of 4% year over year.

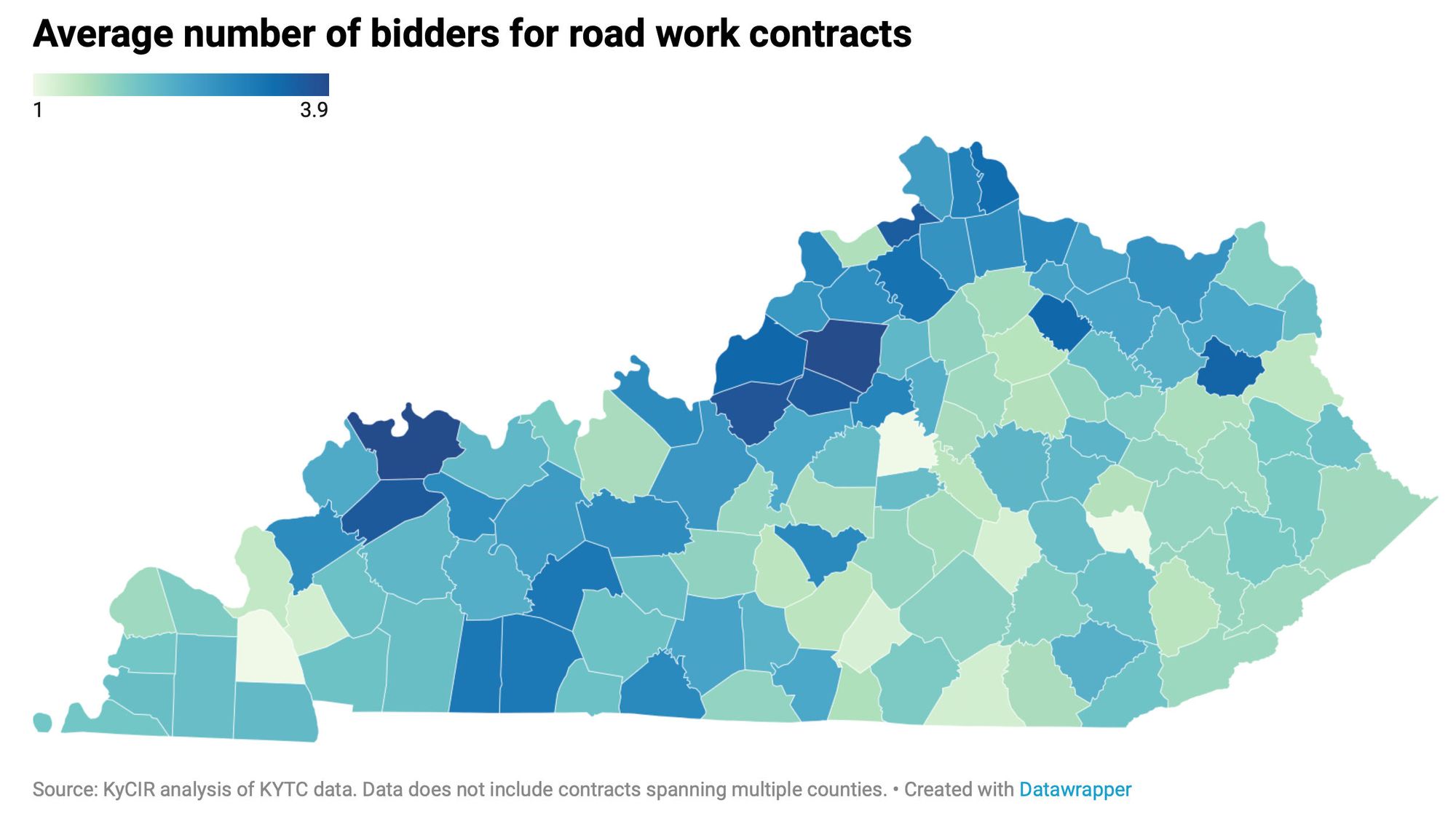

Certain counties in central and eastern Kentucky are more likely to see single-bid contracts awarded to a handful of companies. Jefferson county and portions of Northern Kentucky, on the other hand, average three or more bidders.

In eight Eastern Kentucky counties stretching from Harrison County down to McCreary County on the state’s southern border, the Hinkle Contracting Company is the only contractor to be awarded a state contract this year.

Hinkle Contracting is owned by Summit Materials, a Denver construction conglomerate. Company executives did not respond to an interview request.

Hinkle obtained more single-bid contracts than any other road construction entity in the nearly three years of state data reviewed. The company was the sole bidder on 154 projects totaling more than $87 million — and nearly 60% of those contracts were awarded at a higher cost than state estimates.

In recent years, labor shortages and consolidation in the industry has reduced the number of large contractors vying for government jobs, according to Roy Sturgill, an assistant professor of construction management at Iowa State University.

“Contractors are smart, if they know their most recent competitor got bought by someone else, or they bought them, then they've reduced the pool of people that they're competing against,” said Sturgill, who worked as a transportation engineer for the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet for six years.

With fewer contractors in the market to compete, single bids will at times be inevitable, said Chad LaRue, executive director of the Kentucky Association of Highway Contractors.

And with the steep costs associated with entering the road paving market, any new competition is unlikely — unless it comes via consolidation or an out-of-state entity, he said.

“It’s very capital intensive,” LaRue said. “There is money to be made, but there is also risk.”

‘We don’t have bad contractors’

Asphalt contractors in Kentucky have been under scrutiny for decades.

Leonard Lawson, founder of Kentucky-based Mountain Enterprises, was indicted on antitrust charges in 2008 when federal prosecutors accused him of working with the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet to rig bids in favor of Mountain. A jury acquitted Lawson and his co-defendants — two state transportation cabinet officials, including the then-cabinet secretary, Bill Nighbert.

In 2017, West Virginia’s attorney general accused Mountain Enterprises, now under new ownership, of colluding to raise paving costs with other contractors. The contractors had consolidated under the ownership of Oldcastle Inc., an Ireland-based corporation, and the contractors stopped bidding against each other. The attorney general said that constituted an illegal monopoly that drove up costs.

The case ended with the largest antitrust settlement in state history. The settlement did not require the companies to admit to any wrongdoing.

Companies tied to the Lawson family came under scrutiny once again in 2017 when federal investigators raided the offices of ATS Construction and subsidiaries, all owned by Leonard Lawson’s son, Steve Lawson. The Transportation Cabinet confirmed at the time that it was cooperating with a federal antitrust investigation related to road contracts. It is unclear what became of the investigation and the cabinet didn’t respond to a question about it.

At the legislative hearing last month, the legislators rallied to the industry’s defense.

“We don’t have bad contractors,” said Rep. Sal Santoro, a Republican from Union. “I think we have outstanding contractors.”

Santoro filed a bill last year that proposed, in part, to reject any single bid submitted that’s above the state’s official estimates, but the legislation failed to pass out of committee.

He said single-bid contracts are inevitable. But he believes the state is getting its money's worth in work.

That same year Santoro proposed the change, the state’s largest road contractors spent at least $102,000 employing some of the state’s most influential lobbyists. For example, Hinkle hired McCarthy Strategic Solutions, led by former Republican Party of Kentucky chair John McCarthy, for lobbying the legislative and executive branches.

Sen. Jimmy Higdon, a Republican from Lebanon and chair of the interim transportation committee, said outside pressure is ever present in politics, and he hears from lobbyists everyday.

“To say they control our decisions is not true,” he said. “But do they play a role? Sure.”

State campaign data show that road contractors also play a role in funding political campaigns.

In the past two decades, employees at a dozen of the state’s largest road construction companies contributed more than $1.1 million — the vast majority to gubernatorial and legislative elections, according to Kentucky Registry of Election Finance data.

No candidate received more from road contractor employees than former Republican Gov. Matt Bevin, who reported more than $105,000 in statewide elections.

Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear took more than $30,000 in campaign contributions from the state’s largest road contractors during his bids for state attorney general and governor.

A spokesperson for state auditor Mike Harmon — a Republican candidate for governor who has no record of donations from road construction employees— said he has no plans to pursue an audit of construction contracts without a directive from the legislature.

The legislators who shot down McNeill’s request for an audit last month have taken, collectively, more than $112,000 from road construction firms over their careers.

McNeill, himself a registered lobbyist representing the Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions, thinks politics have helped insulate the industry from scrutiny. “I've seen it done time and time again in Frankfort,” he said.

In an interview a few weeks after the meeting, Higdon, the chair of the committee, said “there’s not enough smoke here” to call for an audit of the state’s process for awarding single-bid contracts.

State transportation cabinet officials provided Higdon prior to the November meeting with data and a sheet of talking points that aimed to defend the state’s bidding process. Higdon said some “give and take” is expected in road construction costs. “And it’s not particularly a problem,” he said.

--30--

Written by Jacob Ryan and Jared Bennett. Cross-posted from the KY Center for Investigative Reporting, via AP Storyshare.