The following is from the newsletter Letters from an American by Heather Cox Richardson. You can sign up for the free version here.

Since the Civil War, voter suppression in America has had a unique cast.

The Civil War brought two great innovations to the United States that would mix together to shape our politics from 1865 onward:

First, the Republicans under Abraham Lincoln created our first national system of taxation, including the income tax. For the first time in our history, having a say in society meant having a say in how other people’s money was spent.

Second, the Republicans gave Black Americans a say in society.

They added the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, outlawing human enslavement except as punishment for crime and, when white southerners refused to rebuild the southern states with their free Black neighbors, in March 1867 passed the Military Reconstruction Act. This landmark law permitted Black men in the South to vote for delegates to write new state constitutions. The new constitutions confirmed the right of Black men to vote.

Most former Confederates wanted no part of this new system. They tried to stop voters from ratifying the new constitutions by dressing up in white sheets as the ghosts of dead southern soldiers, terrorizing Black voters and the white men who were willing to rebuild the South on these new terms to keep them from the polls. They organized as the Ku Klux Klan, saying they were “an institution of chivalry, humanity, mercy, and patriotism” intended “to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States… [and] to aid and assist in the execution of all constitutional laws.” But by this they meant the Constitution before the war and the Thirteenth Amendment: candidates for admission to the Ku Klux Klan had to oppose “Negro equality both social and political” and favor “a white man’s government.”

The bloody attempts of the Ku Klux Klan to suppress voting didn’t work. The new constitutions went into effect, and in 1868 the former Confederate states were readmitted to the Union with Black male suffrage. In that year’s election, Georgia voters put 33 Black Georgians into the state’s general assembly, only to have the white legislators expel them on the grounds that the Georgia state constitution did not explicitly permit Black men to hold office.

The Republican Congress refused to seat Georgia’s representatives that year—that’s the “remanded to military occupation” you sometimes hear about– and wrote the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution protecting the right of formerly enslaved people to vote and, by extension, to hold office. The amendment prohibits a state from denying the right of citizens to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

So white southerners determined to prevent Black participation in society turned to a new tactic. Rather than opposing Black voting on racial grounds—although they certainly did oppose Black rights on these grounds– they complained that the new Black voters, fresh from their impoverished lives as slaves, were using their votes to redistribute wealth.

To illustrate their point, they turned to South Carolina, where between 1867 and 1876, a majority of South Carolina’s elected officials were African American. To rebuild the shattered state, the legislature levied new taxes on land, although before the war taxes had mostly fallen on the personal property owned by professionals, bankers, and merchants. The legislature then used state funds to build schools, hospitals, and other public services, and bought land for resale to settlers—usually freedpeople—at low prices.

White South Carolinians complained that members of the legislature, most of whom were professionals with property who had usually been free before the war, were lazy, ignorant field hands using public services to redistribute wealth.

Fears of workers destroying society grew potent in early 1871, when American newspaper headlines blasted the story of the Paris Commune. From March through May, in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, French Communards took control of Paris. Americans read stories of a workers’ government that seemed to attack civilization itself: burning buildings, killing politicians, corrupting women, and confiscating property. Americans worried that workers at home might have similar ideas: in italics, Scribner’s Monthly warned readers that “the interference of ignorant labor with politics is dangerous to society.”

Building on this fear, in May 1871, a so-called taxpayers’ convention met in Columbia, South Carolina. A reporter claimed that South Carolina was “a typical Southern state” victimized by lazy “semi-barbarian” Black voters who were electing leaders to redistribute wealth. “Upon these people not only political rights have been conferred, but they have absolute political supremacy,” he said. The New York Daily Tribune, which had previously championed Black rights, wrote “the most intelligent, the influential, the educated, the really useful men of the South, deprived of all political power,… [are] taxed and swindled… by the ignorant class, which only yesterday hoed the fields and served in the kitchen.”

The South Carolina Taxpayers’ Convention uncovered no misuse of state funds and disbanded with only a call for frugality in government, but it had embedded into politics the idea that Black voters were using the government to redistribute wealth. The South was “prostrate” under “Black rule,” reporters claimed. In the election of 1876, southern Democrats set out to “redeem” the South from this economic misrule by keeping Black Americans from the polls.

Over the next decades, white southerners worked to silence the voices of Black Americans in politics, and in 1890, fourteen southern congressmen wrote a book to explain to their northern colleagues why Democrats had to control the South. Why the Solid South? or Reconstruction and its Resultsinsisted that Black voters who had supported the Republicans after the Civil War had used their votes to pervert the government by using it to give themselves services paid for with white tax dollars.

Later that year, a new constitution in Mississippi started the process of making sure Black people could not vote by requiring educational tests, poll taxes, or a grandfather who had voted, effectively getting rid of Black voting.

Eight years later, there was still enough Black voting in North Carolina and enough class solidarity with poor whites that voters in Wilmington elected a coalition government of Black Republicans and white Populists. White Democrats agreed that the coalition had won fairly, but about 2000 of them nonetheless armed themselves to “reform” the city government. They issued a “White Declaration of Independence” and said they would “never again be ruled, by men of African origin.” It was time, they said, “for the intelligent citizens of this community owning 95% of the property and paying taxes in proportion, to end the rule by Negroes.”

As they forced the elected officials out of office and took their places, the new Democratic mayor claimed “there was no intimidation used,” but as many as 300 African Americans died in the Wilmington coup.

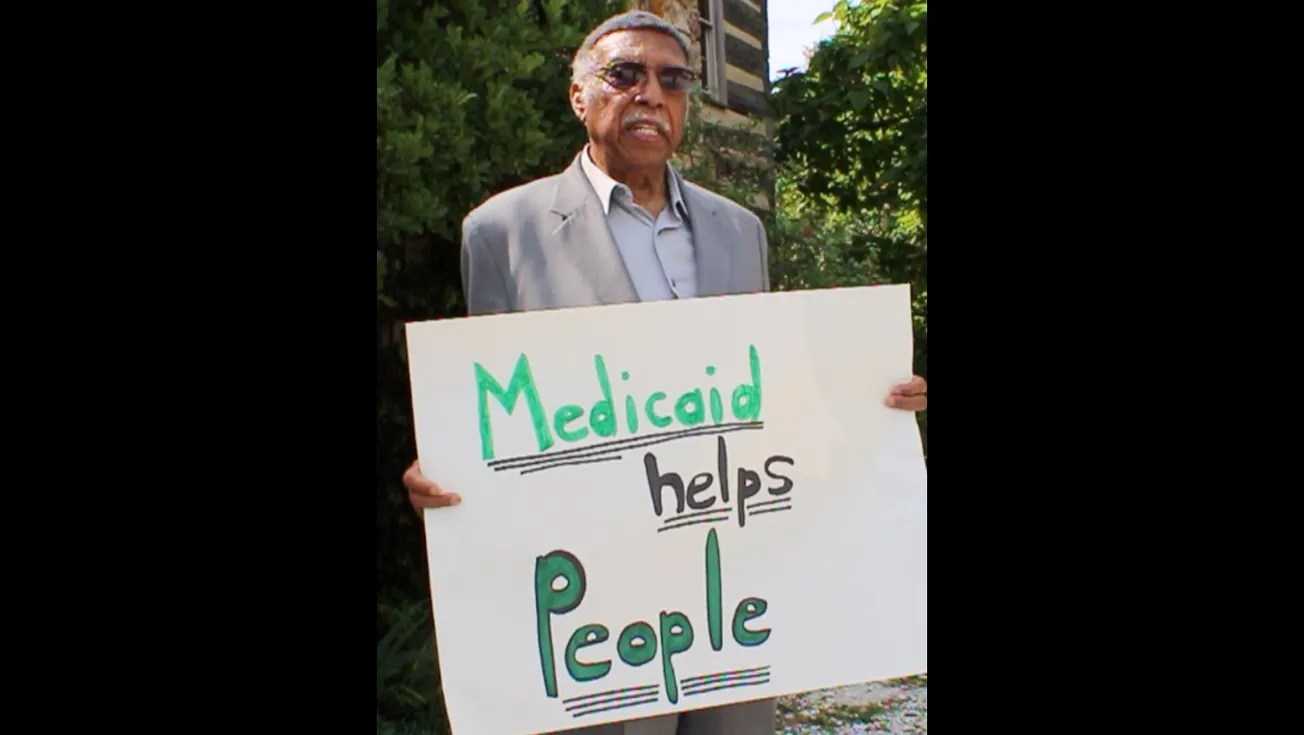

The Civil War began the process of linking the political power of people of color to a redistribution of wealth, and this rhetoric has haunted us ever since. When Ronald Reagan talked about the “Welfare Queen (a Black woman who stole tax dollars through social services fraud), when tea partiers called our first Black president a “socialist,” when Trump voters claimed to be reacting to “economic anxiety,” they were calling on a long history. Today, Republicans talk about “election integrity,” but their end game is the same as that of the former Confederates after the war: to keep Black and Brown Americans away from the polls to make sure the government does not spend tax dollars on public services.

–30–

Notes: I don’t link to my own books usually, but if anyone is interested, the argument and quotations here are from my second book, “The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post-Civil War North,” (Harvard University Press, 2001).