Written by Katelyn Jetelina, who writes as “Your Local Epidemiologist.”

Firearms are the leading cause of death for American children. But, like any public health problem, the risk is not equally distributed. Who is dying, how, and where? Here are the epidemiological patterns, which can help parents and communities move the needle.

Where are children dying?

The rate of firearm mortality in children is by far the highest in the U.S., compared to any other country in the world. We have access to a lot more guns than people in other countries: there are ~120 firearms per 100 people in the U.S. (Yemen is the second highest with 52 per 100 followed by Serbia at 39 per 100).

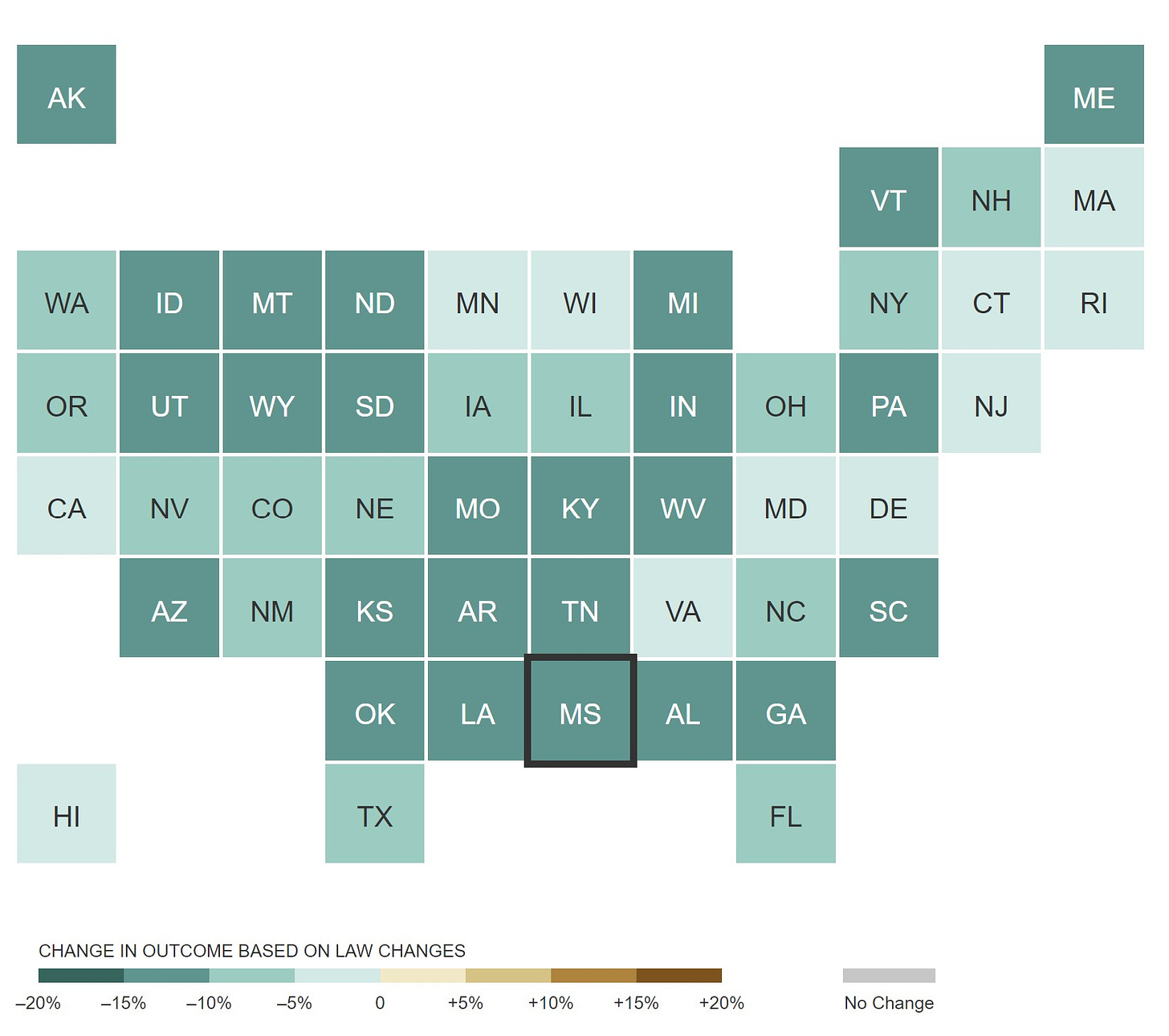

Within the U.S., there are striking differences across states. For example, among 14 to 24 year olds, Mississippi’s firearm death rate is 7 times higher than Massachusetts (42 vs. 6 per 100,000 people). DC has the highest rate of firearm deaths at 72 per 100,000 young people ages 14 to 24.

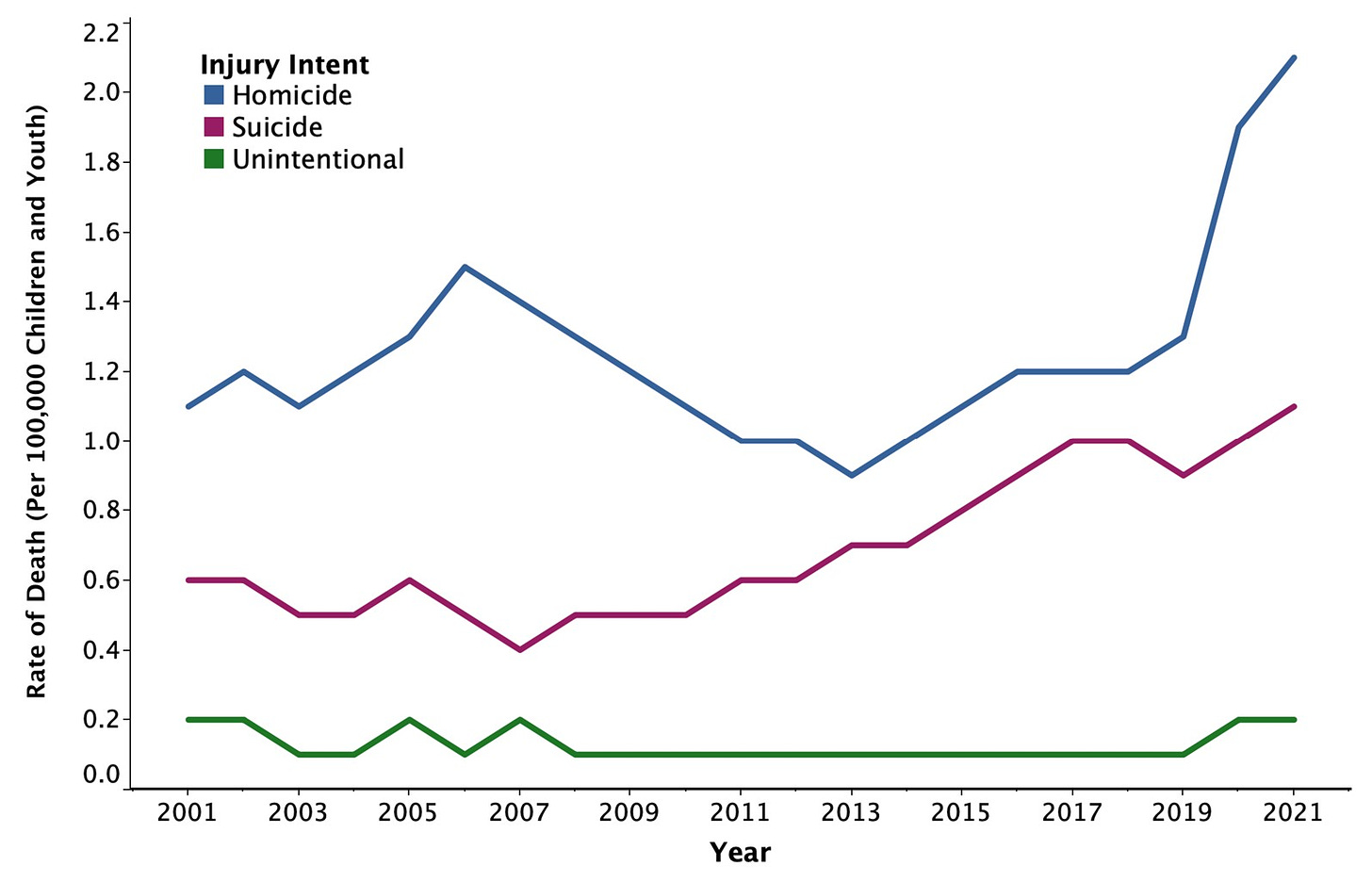

How are children dying?

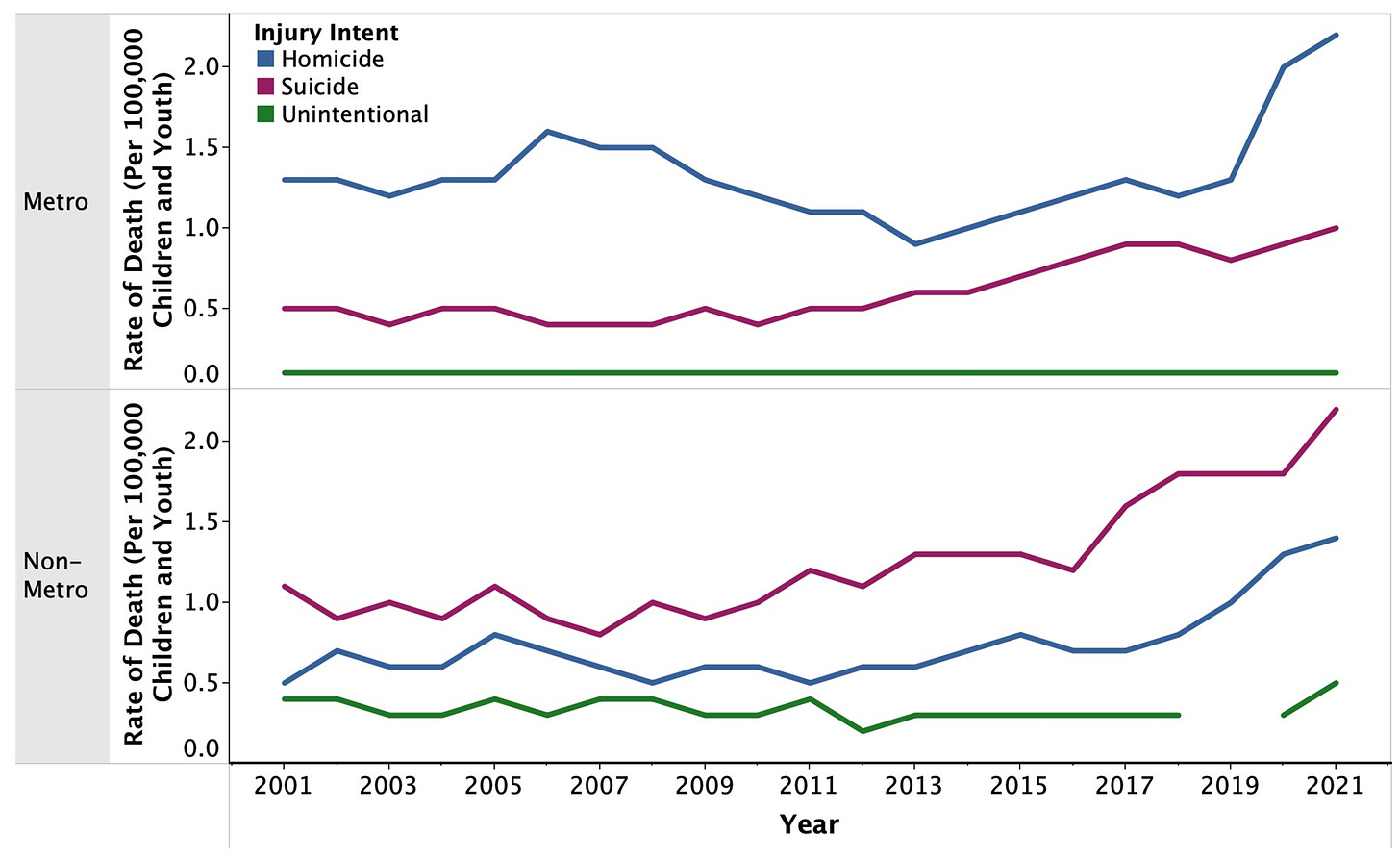

Homicides account for the most firearm deaths among children. This took off during the pandemic. Suicide has been closely inching up for years. Unintentional deaths, like when a curious child finds a gun in the nightstand, contribute to ~5% of firearm deaths. Mass shootings account for <1% of firearm deaths among children.

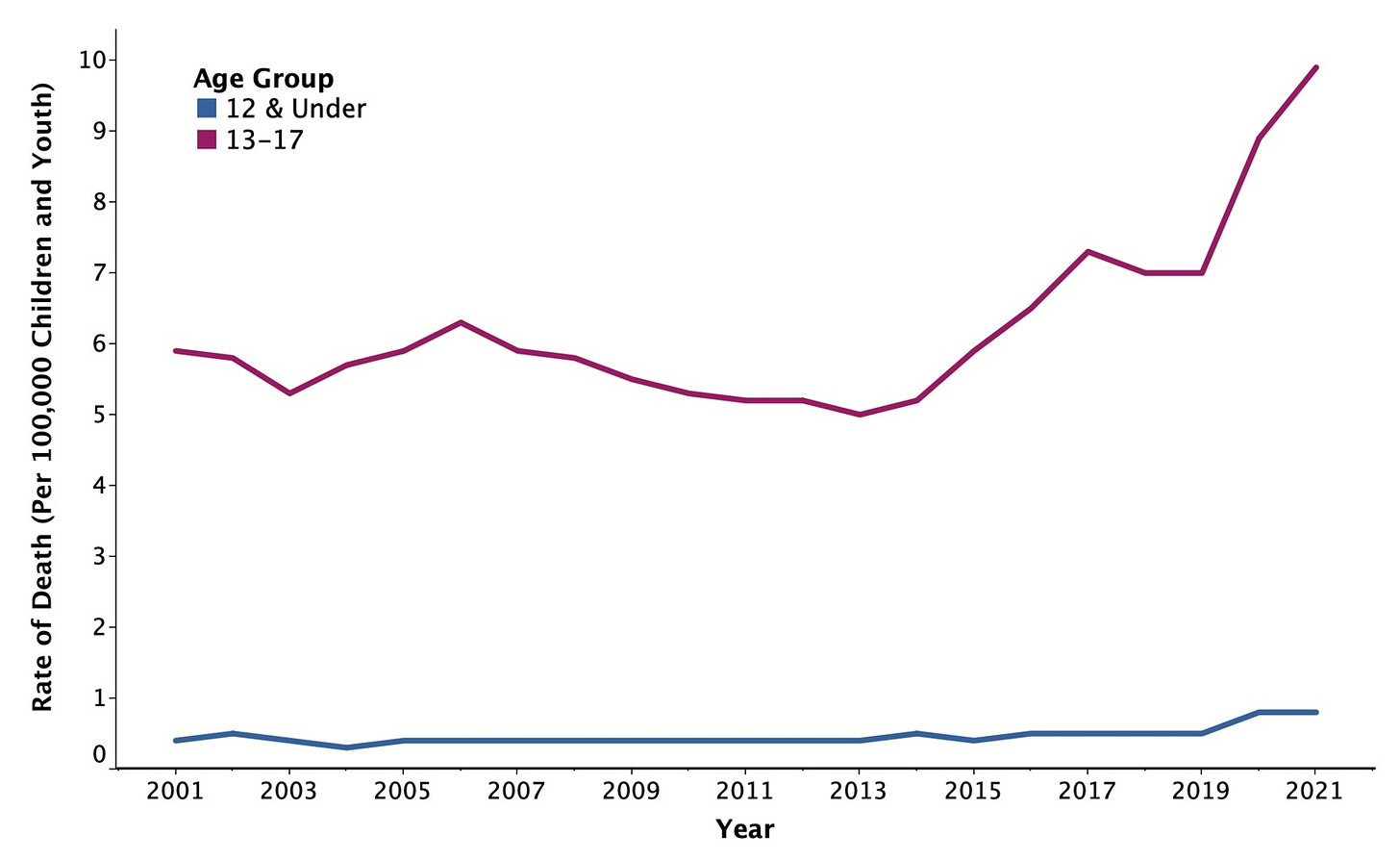

Who is more likely to die?

Guns affect every demographic, but some groups are more impacted.

Age: Older children more often die from firearms than younger children.

Race/ethnicity: Black or African American children die from homicide and unintentional injury far more often than any other group. Suicides are most common among American Indian/Alaska Native children (see blue dot below), followed by White children.

Urban/rural: The overall rate of firearm deaths in children is about the same in both urban and rural areas. However, the most common reasons are completely switched. In urban areas, children are more likely to die from homicides, while in non-metro areas, children are more likely to die from suicide.

How to protect children on an individual level?

There’s a lot we can do. But the lowest hanging, evidence-based fruit: safe storage.

1 in 3 youth suicides and unintentional deaths can be prevented by securing guns. People are at an increased risk for homicide when there is a gun in the home, too.

This is because 42% of homes have at least one firearm and 4.6 million kids live with unlocked, loaded guns.

This means:

- Firearm owners need to focus on safe storage. Change cultural norms around what safe, responsible firearm ownership looks like.

- Non-firearm owners need heightened awareness of guns in other people’s homes. There’s a 1 in 3 chance your kid is going to a friend’s house where there are firearms. Just as you’d ask about supervision before your child visits another home, ask one more important question: “Is there an unlocked gun in your house?”

The second lowest hanging fruit: red flags. Make sure children are comfortable coming to you with concerns. If you’re not there, ensure there’s another family member or trusted friend there for them. At the same time, understand risk factors that lead to crises and signs that someone is in a crisis.

How to protect children on a population level?

Policy is a huge catalyst in public health—think seatbelts, DUIs, and non-smoking areas.

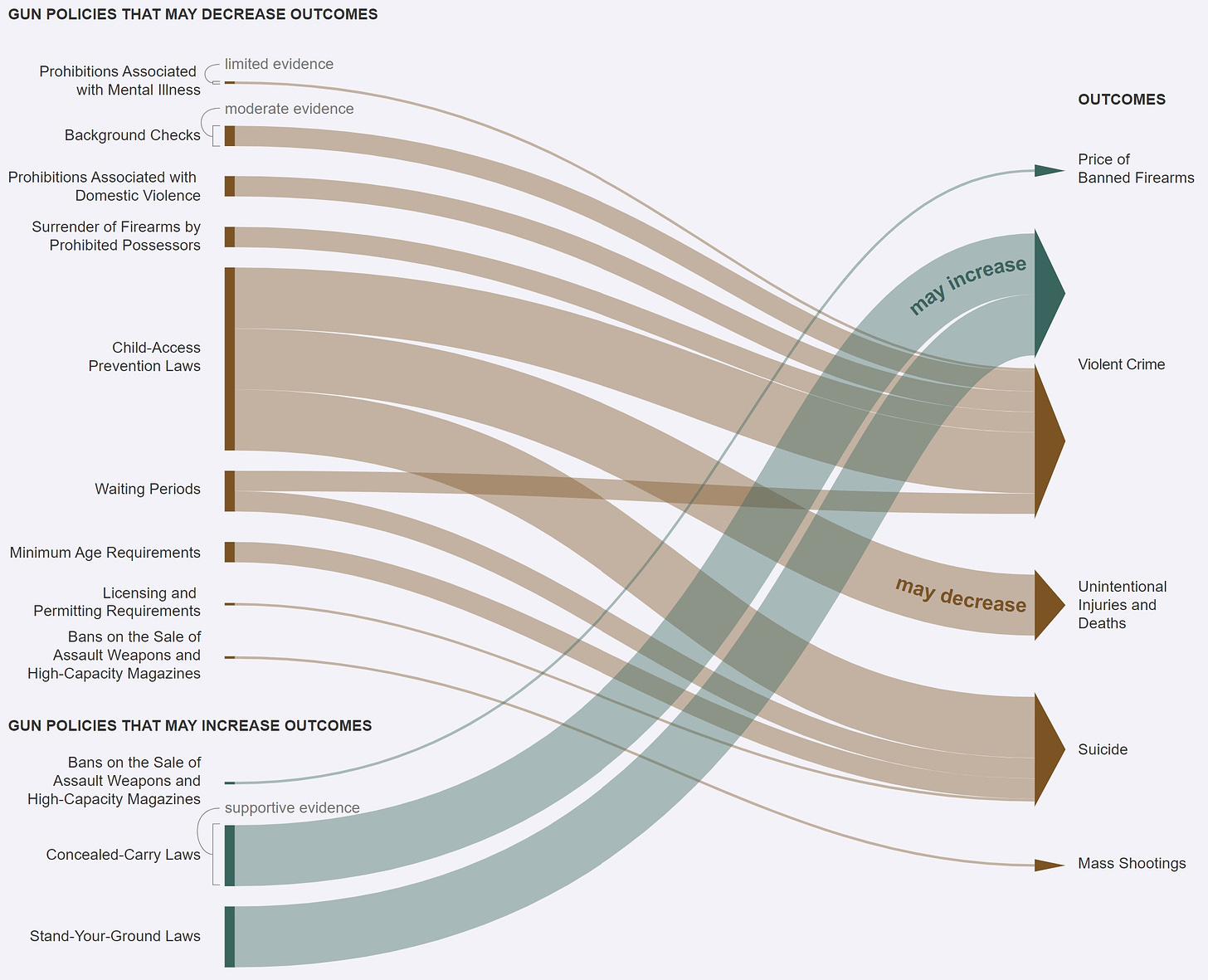

RAND has an excellent data explorer on gun policy impact. The policy with the most evidence: child access prevention, with civil or criminal penalties for storing a handgun in a manner that allowed access by a minor.

Studies have shown passing such laws may reduce firearm suicides, although firearm homicides are expected to decline, too. If this went into effect in Mississippi, for example, we would expect firearm deaths to decline by 13%.

Although this policy has the most evidence, it’s not necessarily what the most people agree on. There is bipartisan support for other common sense gun policies, including red flag laws.

Bottom line

Firearms are the primary source of mortality for American children, which is mainly driven by suicide and homicide. There are things we can do to help protect our kids from being the next statistic.

Love, YLE

--30--

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD – an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To subscribe, go here.