Table of Contents

The relationships between state and local governments in the U.S. have changed many times. In recent years, however, one change has become both relevant and troubling: the dramatic rise in state preemption of local laws.

Preemption is the process in which a higher level of government creates a law or policy which supersedes a law or policy from a lower level of government. While this concept is not new, the use of preemption is increasing.

Gridlock or failure to address problems at the state and federal level can cause local leaders to try new, often progressive policies. In this sense, local governments have supplanted states as what Louis Brandeis called “laboratories of democracy.”

And for the most part, citizens like the results. People consistently trust local government more than state governments (though both are substantially higher than trust in the federal government).

Many of these progressive policies have created a backlash from corporate interests. Major preemption efforts were undertaken in the 90s in response to smoking bans and gun laws. These efforts were led by lobbyists from the NRA and R.J. Reynolds. However, the surge in preemption really began after the 2010 elections, with each year since 2011 seeing more preemption activity than the year before. Thirty-six states have passed preemption laws since last year.

In the traditional sense, laws from higher levels of government established a policy floor or minimum. If the federal minimum wage was at a certain level, any state minimum wage had to be at least at the level, but could be higher. Pollution standards must meet a certain minimum level, but could be more stringent.

Preemption trades the idea of a policy floor for that of a policy ceiling, establishing a policy standard and telling local governments they can do no more. In many instances, states prevent local governments from regulating certain actions, banning cities from banning plastic bags, for instance (a ban ban).

[tweet_box design=”default” float=”none”]Preemption trades a policy floor for a policy ceiling – and that hurts us all.[/tweet_box]

Preemption is typically counterproductive, however. It is a threat to local success, limiting cities’ ability to regulate their own economies and expand rights.

Much has been said about how this highlights the rural/urban divide, and that is certainly a factor. But preemption does not just stop with “big” cities. Preemption isn’t just about Louisville or Lexington. Kentucky has 120 counties and hundreds of cities. Every one of those entities is threatened by preemption.

In the last legislative session in Frankfort, we saw what was called the “war on Louisville.” But the issue is bigger than that. This is quickly becoming a nationwide “war on cities.” This is especially true in Texas, where their Governor has advocated for a “ban across the board” on local regulations.

Some states have even begun using so called “super preemption.” A Florida statute holds that, not only does state law pre-empt local law, but local officials who even attempt to pass gun control laws can be fined and removed from office (although Tallahassee mayor and gubernatorial candidate Andrew Gillum has not been shy about challenging this).

Examples of Preemption

The most well-known example of preemption is North Carolina’s HB2. Commonly referred to as simply the “bathroom bill,” this law preempted local ordinances regarding the use of bathroom facilities and preempted local ordinances regarding the minimum wage.

But while North Carolina’s bill captured the nation’s attention, preemption legislation has spread to a vast majority of states and to almost every policy field.

The most common example may be laws regulating minimum wage increases in urban areas. In addition to North Carolina, Kentucky’s Supreme Court ruled that Lexington and Louisville do not have the authority to increase their minimum wages, as state law already exists and is thus supreme. Alabama passed a bill to block minimum wage increases the day after Birmingham voted to increase theirs. In a particularly cruel piece of legislation, Missouri preempted a St. Louis ordinance which had already raised the minimum wage, effectively cutting the salaries of many workers by $2.30 an hour.

The range of policy topics that have been affected extends beyond wages. States have preempted cities on combating climate change and banning plastic bags. Many states have stopped cities from passing gun laws, despite cities being where most gun crimes occur. Arizona has preempted cities from banning Happy Meal Toys and has even banned Phoenix from banning puppy mills.

States have been using preemption to stop cities from removing Confederate monuments, even those in municipal parks. When Birmingham was prevented from removing one, they covered it up with a barrier. The Alabama Attorney General promptly sued the mayor and the city. These laws exist in several states.

The list goes on. From fracking to drones to fire sprinklers, if it’s a problem, someone somewhere is trying to stop a city from fixing it.

Motives Behind Preemption

So, what is behind this recent wave of preemption laws? The urban/rural divide certainly plays a role, as does a similar liberal/conservative divide. But these have existed for some time, and don’t explain why preemption has become the go to policy route.

Industry-backed efforts likely play a greater role. This is true of pretty much any industry. But these efforts have also been going on for a long time, and don’t fully explain the current preemption bubble we are in.

The biggest cause of the increase in preemption policies is most likely our friends at ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council. ALEC has been getting heavily involved with state legislatures, with legislation models for preempting local laws on pesticides, wages, labor relations, and rent. ALEC has even put out a very patronizing, selective interpretation of federalism and the rights of cities.

Over the past few years, however, ALEC has been going after city halls directly. The American City County Exchange (ACCE) is the local government arm of ALEC, and though it is relatively new, it has had some success in Kentucky fighting unions through right to work legislation at the county level. If ALEC and ACCE keep going, there may not be any progressive laws left to preempt.

Issues with Preemption

There are several issues with preemption: some philosophical, some social, and some economic.

One issue with preemption is that those using it the most (Republicans) are the ones who bristle at the idea of federal interference. You would think Republicans who espouse devolution would find the idea of empowering cities philosophically appealing. However, they seem to be arguing that government should be close to the people, but not too close. Andrew Gillam, the mayor of Tallahassee, said that when Republicans support local government, “they only mean that to the extent that they’re in control.”

[bctt tweet=”Republicans support local control only when they are the ones in control.” username=”ForwardKY”]

Several Republican legislators have said as much. One Ohio State Senator stated “so when we talk about local control, we mean state control.” Showing a further lack of concern for local control, a State Representative from Florida argued that “we’re the United States of America. We are not the United Towns of Florida. We’re not the United Counties of Florida.”

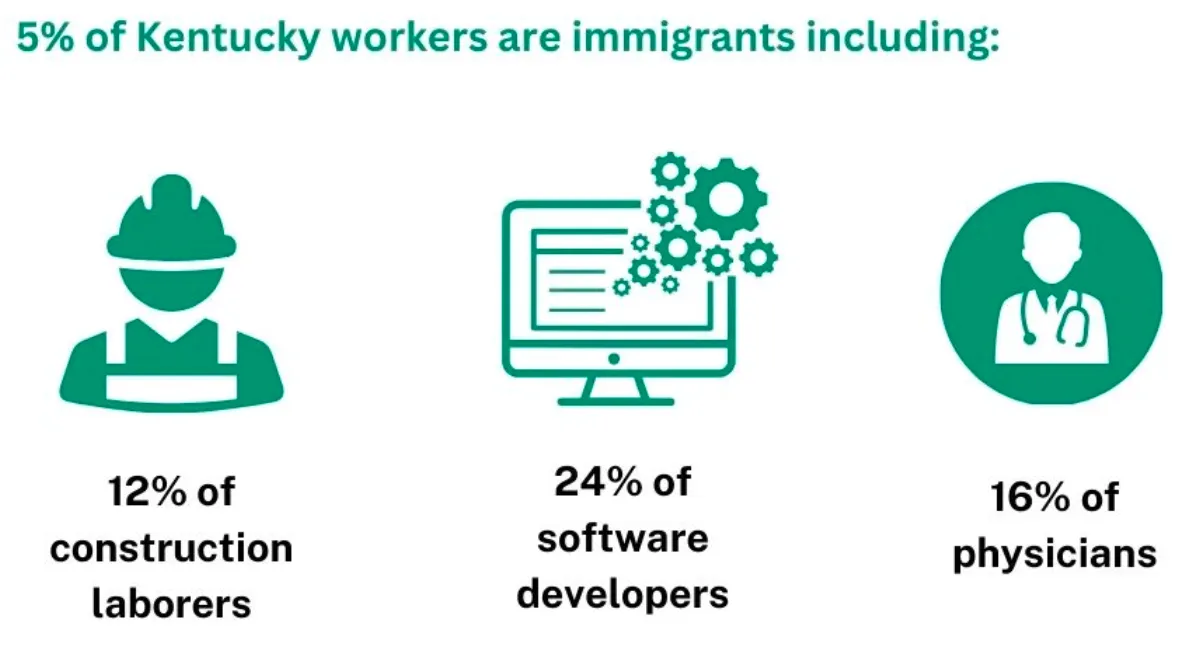

Another issue which often goes overlooked in these debates is the racial component. It is the case with most preemption efforts that mostly white legislatures overrule laws passed by areas with more minority residents. And many of these efforts have focused on issues such as freezing or reducing the minimum wage, which disproportionately affect minority citizens. This has the dual effect of stripping minorities of both political and economic power.

There are also economic concerns. Many who support preemption measures do so to prevent what they call a “patchwork quilt” of regulations. If different cities have different wages, different pollution standards, different safety standards, etc., it will be confusing for businesses. Others take the more traditional argument that things like minimum wage increases and paid family leave are bad for business.

Of course, these arguments are incorrect. Businesses chose where to locate for several reasons, including access to markets, a skilled workforce, infrastructure, and agglomeration forces. And if a business is only coming to your state so they can take advantage of your workers and pollute your environment, they aren’t the kind of businesses states should really be chasing.

Preemption cuts off economic opportunity and causes business to leave the state, not come to it. Despite the pro-business arguments, North Carolina’s HB2 cost the state hundreds of millions of dollars and thousands of jobs (including the Governor’s). In the coming years, it’s estimated that the state will lose nearly $4 billion because of the law. Texas, which has its own version of North Carolina’s law, SB6, has already seen enormous pushback from the business community, with officials from Chevron, Dow, BBVA, ExxonMobil, Halliburton, ConocoPhillips, and many others coming out against it.

Some Examples of Good Preemption

Further complicating the debate is the fact that not all examples of preemption are inherently bad. In Oregon, for example, a House Bill was put forth which would have made it harder for local governments to restrict affordable housing. It did not pass, but in areas like Portland which are experiencing a severe housing affordability crisis, this sort of preemptive action could have positive results.

California is also addressing this issue. Legislation has been introduced which would streamline housing in areas without enough supply. This in in addition to preemption of local laws regarding so called “in-law” units last year.

Sometimes states really do need to step in. But the recent glut of preemption action has seen state legislatures dramatically overestimate this need.

Options for Cities

So, what can cities do in this era of preemption? They could lobby the state, which may be more effective if other cities join in. It’s become too easy politically for Kentucky to stick a finger in the eye of Louisville, but if Louisville and Lexington and Paducah and Richmond and London all showed up, that may be a little harder for the legislature to ignore.

Of course, city leaders could work toward their goals anyway. If the state preempts you on the minimum wage, lead by example and raise the wage for city employees.

They can also work with other cities to try and accomplish their goals. Cities are already coming together to handle climate change and other large policy issues that the nation is not addressing. Last year, the Global Parliament of Mayors was formed. With these steps, it is likely that intercity relationships will grow stronger, even if the relationship between cities and their states remains adversarial.

Cities could also pursue legal avenues. Cleveland won a preemption case in court concerning local hiring laws by citing Ohio’s Home Rule mandate. Pennsylvania lost a case regarding the preemption of fracking bans.

One group of local lawmakers, led by Andrew Gillum, have established an organization fighting for the ability to enact local solutions to problems, with resources to help cities deal with state preemption.

A more combative route was mentioned by Benjamin Barber, who suggested a large number of cities could simply withhold paying taxes when faced with preemption from higher levels of government. Cities do create most of a state’s GDP, and what they lack in political strength they more than make up for economically.

Most of these options are confrontational though. They assume that cities and states are fundamentally at odds with each other. The simplest option would be to elect state leaders with the wisdom to know when to intervene and when to let cities implement their own policies. Home Rule could be expanded and strengthened so that local governments have the ability to enact policies that fit their specific needs.

This doesn’t have to be a fight. It’s OK that not everyone lives in the same type of community. It makes our state stronger. As Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians:

If the whole body were an eye, where would the hearing be? If the whole body were hearing, where would the sense of smell be? … As it is, there are many members, yet one body. The eye cannot say to the hand, “I have no need of you,” nor again the head to the feet, “I have no need of you.” … If one member suffers, all suffer together with it; if one member is honored, all rejoice together with it.

The city cannot say to the rural areas “I have no need of you,” nor again the rural to the urban. If one part of the state suffers, all suffer together with it; if one part is honored, all rejoice together with it.

Preemption of local laws in recent years has mostly been counterproductive. Even so, it is likely that this trend will continue at least in the short term. While state governments should intervene in certain situations, in most cases they should allow local governments to make the decisions that are best for their citizens. We should call on our elected officials to use good judgment to know the difference. Doing otherwise will hurt our economy and hinder our ability to protect people’s rights.

–30–