In an era of networks knowingly lying about elections, and politicians planning coups in plain sight, we desperately need freedom of speech and press to counter the Big Lies.

Did you know that the US ranks number 43 out of 180 countries on the World Press Freedom Index? That’s right – 42 other countries, including Ghana, South Africa, and Jamaica, are judged by ‘Reporters Without Borders’ to have greater press freedom than the United States, whose freedom of press is enshrined in our 1st Amendment.

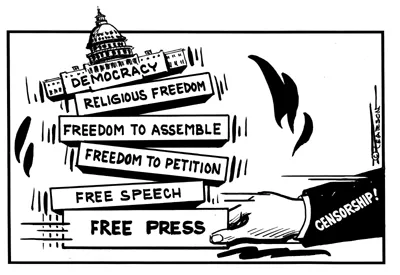

Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo declared more than 80 years ago, “Freedom of speech is the indispensable condition of nearly every other form of freedom.”

In his article “The Ongoing Challenge to Define Free Speech,” Stephen J. Wermiel writes, “Debate continues about the meaning of freedom of speech and its First Amendment companion, freedom of the press.

“The Supreme Court has interpreted ‘speech’ and ‘press’ broadly as covering not only talking, writing, and printing, but also broadcasting, using the Internet, and other forms of expression. The freedom of speech also applies to symbolic expression, such as displaying flags, burning flags, wearing armbands, burning crosses.”

Geoffrey R. Stone, the Distinguished Service Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, writes, “The Supreme Court has held that restrictions on speech because of its content generally violate the First Amendment. Laws that prohibit people from criticizing a war or advocating for higher taxes on the rich are examples of unconstitutional content-based restrictions. Such laws are thought to be especially problematic because they distort public debate and contradict a basic principle of self-governance: that the government cannot be trusted to decide what ideas or information ‘the people’ should be allowed to hear.”

The case of John Peter Zenger

One of the most important legal cases in the Founders’ understanding of the freedom of the press happened in 1735 in New York state. Karl Grossman lays out the details in this article:

Zenger, publisher of the New-York Weekly Journal, was found not guilty of seditious libel by a 12-member jury at a two-day trial that began on August 4, 1735.

The charge was brought by a tyrannical colonial governor of New York, William Cosby, who accused Zenger of printing “false, scandalous, malicious and seditious” articles. The New York-Weekly Journal had been going after the governor, exposing his shady machinations.

Zenger, who had been jailed for nine months, was represented by Andrew Hamilton, considered the foremost lawyer in the colonies. Hamilton took the case pro bono, riding to the rescue from Pennsylvania where he had been former attorney-general.

Hamilton confounded the prosecution by admitting that Zenger had published the offending material, but he took the position that what was involved was the truth. Chief Justice James Delancey, a Cosby henchman, didn’t agree with the defense of truth.

But Hamilton’s response was that: “Leaving it to judgement of the court whether the words are libelous or not in effect renders juries useless.”

On August 5, Hamilton addressed the jury in an eloquent, brilliant summation. ... He said: “Men who injure and oppress the people under their administration provoke them to cry out and complain, and then make that very complaint the foundation for new oppressions and prosecutions. ... The question before the court and you, gentlemen of the jury, is not of small or private concern. It is not the cause of one poor printer, nor of New York alone, which you are now trying. No! It may in its consequence affect every free man that lives under a British government on the main of America. ... It is the best cause. It is the cause of liberty. ... Nature and the laws of our country have given us a right to liberty of both exposing and opposing arbitrary power, in these parts of the world at least, by speaking and writing truth.”

The jury, after a short deliberation returned, and jury foreman Thomas Hunt, asked by the court clerk for its verdict, declared: “Not guilty.”

There were cheers in the courtroom. Judge Delancy, frustrated and angry, threatened the delighted spectators. The jubilant crowd headed to Black Horse Tavern to celebrate. On his return to Philadelphia, Hamilton was also happily welcomed with a cannon salute.

The New York Times, on the 250th anniversary of the Zenger trial, editorialized, “The Zenger case planted the seeds that flowered a half-century later in the First Amendment,” and “across the ages, the Zenger jury registered the public’s understanding that the freedom of the press to challenge authority and convey complaints of the citizenry is indispensable in a free society.”

Ever since Johann Gutenberg invented the printing press nearly 600 years ago now, there have been many in power who feel threatened by people’s free speech and press, and they have worked hard to prevent that.

What should happen when a public official interferes with freedom of speech and press by using their position to put a chill on information the public has a right to know?

Freedom of the press ... in Kentucky

Right here in Kentucky recent documents and emails from Murray State University (MSU), a regional state school in Murray, Kentucky, revealed the provost and the dean of the business school had fought against releasing unflattering news, and that the MSU president had pressured campus radio station WKMS to ‘squash’ the stories.

The NPR-affiliated station was forced to stop some investigative reporting: alleged “likes” of pornographic materials on a social media account; a sexual harassment case involving two Republican state senators; and unflattering accounts of a district judge parading around a courthouse in his underwear after hours. All complained to the university president about the WKMS reporting.

WKMS journalists faced obstacles as they worked to gather facts to report these stories. These stories were especially important for the local community to know, as it was an election year.

After attempts to block WPSD, a regional television station in western Kentucky, from getting information about these stories, the station filed open records requests with the Attorney General. When the records were finally given to the station, they produced hundreds of emails and other documents that shone a light on these stories.

What was revealed was how the President actively rejected a distinguished grant to fund a reporter position with WKMS Radio, and continually requested through the Provost and administration officials to intimidate the WKMS management and journalists to “cease and desist” from publishing any stories that would reflect negatively on the local politicians and the university.

A free press: the antidote to abuse of power

The Republican super-majority in our legislature has passed a variety of laws that repeal transparency – laws that allowed constituents and the media to shine a light on behaviors of politicians and government officials. This has trickled down to local governments, including state university administrations.

The old proverb says that “Power corrupts – and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Without a free press to watch the powerful, this proverb plays itself out time and again.

The founders included freedom of speech and freedom of the press in the Constitution for a number of reasons, but one was very clear: “whereby oppressive officers are shamed or intimidated into more honorable and just modes of conducting affairs.”

Whenever an authoritarian takes over a nation, one of the first things they do is get rid of the free press. Whenever public officials are engaged in questionable acts, the last thing they want to see is a reporter on their doorstep.

So in this day of brazen corruption in government, in business, and in our public and private institutions, let us hold on to one of the key weapons to fight that corruption: the free press.

--30--

Written by John James Alexander, a pseudonym for a long-time Kentucky educator.

Comments