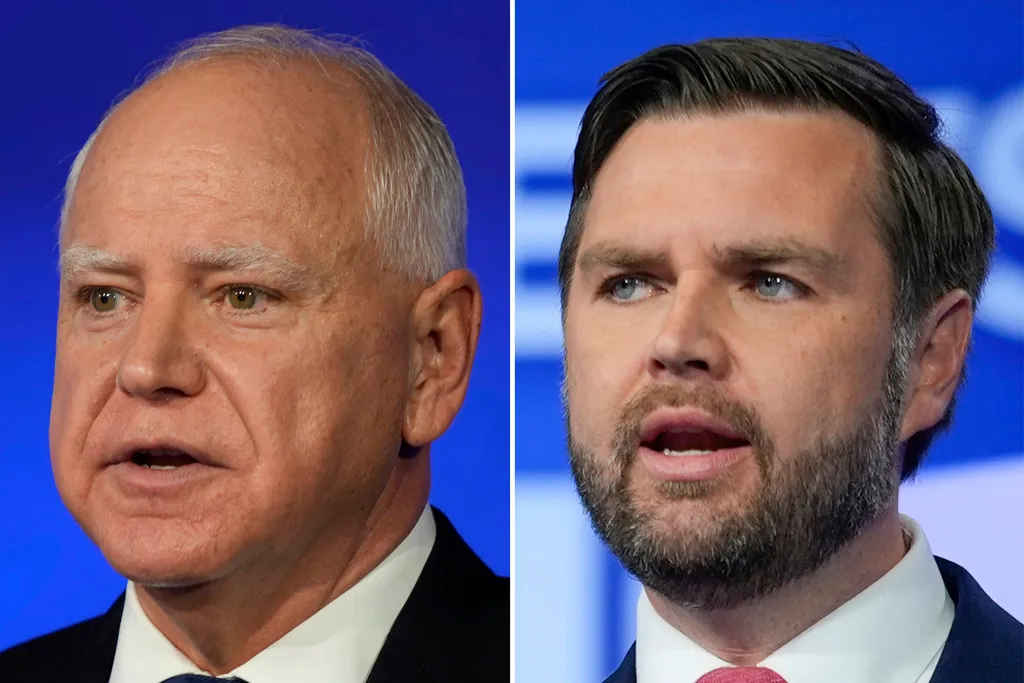

It was Gov. Tim Walz’s Freeport moment.

At the end of the VP debate, he asked Sen. JD Vance if Trump lost the 2020 election. Vance sidestepped the question.

Walz vanquished Vance with a knockout reply: “That is a damning non-answer.”

Likewise, Abraham Lincoln skunked Stephen A. Douglas at Freeport, Ill., in the second of their famous 1858 series of Senate debates. More on how in a minute.

Douglas, a Democrat and a powerful U.S. Senator, was a skilled debater. Lincoln was a country lawyer and former state legislator whose only Washington experience was a single House term.

Douglas, also a high-powered Chicago lawyer, probably figured he’d make short work of the bumpkin Lincoln. Maybe the slick, Yalie Vance thought the same of Coach Walz.

Anyway, the Illinois Senate campaign’s main issue was the expansion of slavery into the federal territories. Lincoln and the Republicans opposed the spread of Dixie’s peculiar institution. Douglas championed “popular sovereignty,” or letting the citizens of a territory vote slavery in or out.

But the year before, the Supreme Court had ruled in Dred Scott v Sandford that Congress couldn’t keep slavery out of the territories. In one of its most notorious decisions ever, the high court also said even free Blacks couldn’t be citizens.

For Douglas the stakes were higher than another Senate term. He aimed to turn his reelection into a presidential run in 1860.

Lincoln knew of Douglas’s ambitions and laid a trap for his opponent. Explained historian James M. McPherson in his bestselling book, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era: “Was there any lawful way, Lincoln asked at Freeport, that the people of the territory could exclude slavery if they wished to do so? The point of the question, of course, was to nail the contradiction between Dred Scott and popular sovereignty.”

The senator was caught, and he knew it. “If Douglas answered No, he alienated Illinois voters and jeopardized his reelection to the senate,” McPherson wrote. “If he answered Yes, he alienated the South and lost their support for the presidency in 1860.”

Douglas had been forced to address the issue before, according to the historian. But the debates were being publicized nationally in newspapers, and Lincoln wanted the whole country, not just the debate crowd, to hear his opponent’s response.

McPherson wrote that “Lincoln knew how he would answer the question: ‘He will instantly take ground that slavery cannot actually exist in the territories, unless the people desire it, and so give it protective territory legislation.’”

Douglas’s answer, called the Freeport Doctrine, was enough to save his Senate seat. The Democratic-majority Illinois legislature voted him back to Washington. But as Lincoln expected, his equivocation cost him the slave state South.

In 1860, the Democratic party split into Northern and Southern factions over slavery’s expansion. The Northern Democrats went with Douglas, the Southern Democrats with Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky. John Bell ran as a Constitutional Unionist.

Lincoln won the Republican nomination and the election.

Though a debate moderator, not Walz, asked Vance about the 2020 election, Walz didn’t miss the opportunity to pounce. Vance’s inartful dodge is all over today’s news.

Like Douglas, Vance found himself in a damned-if-I-do- damned-if-I-don’t box. Trump would have blown a fuse had Vance admitted he lost in 2020. Who knows, Trump might have booted Vance off the ticket.

But Vance didn’t say Trump won, and The Donald demands absolute loyalty from his courtiers. So was Vance’s equivocation enough to please his master? Will Trump consider it half heresy at least? We may never know for sure.

Meanwhile, little Freeport came to the Big Apple Tuesday night.

--30--