Hal Jake Allison left Paducah for the Navy in 1939.

He’s coming home Friday for burial in the city’s Maplelawn Park Cemetery.

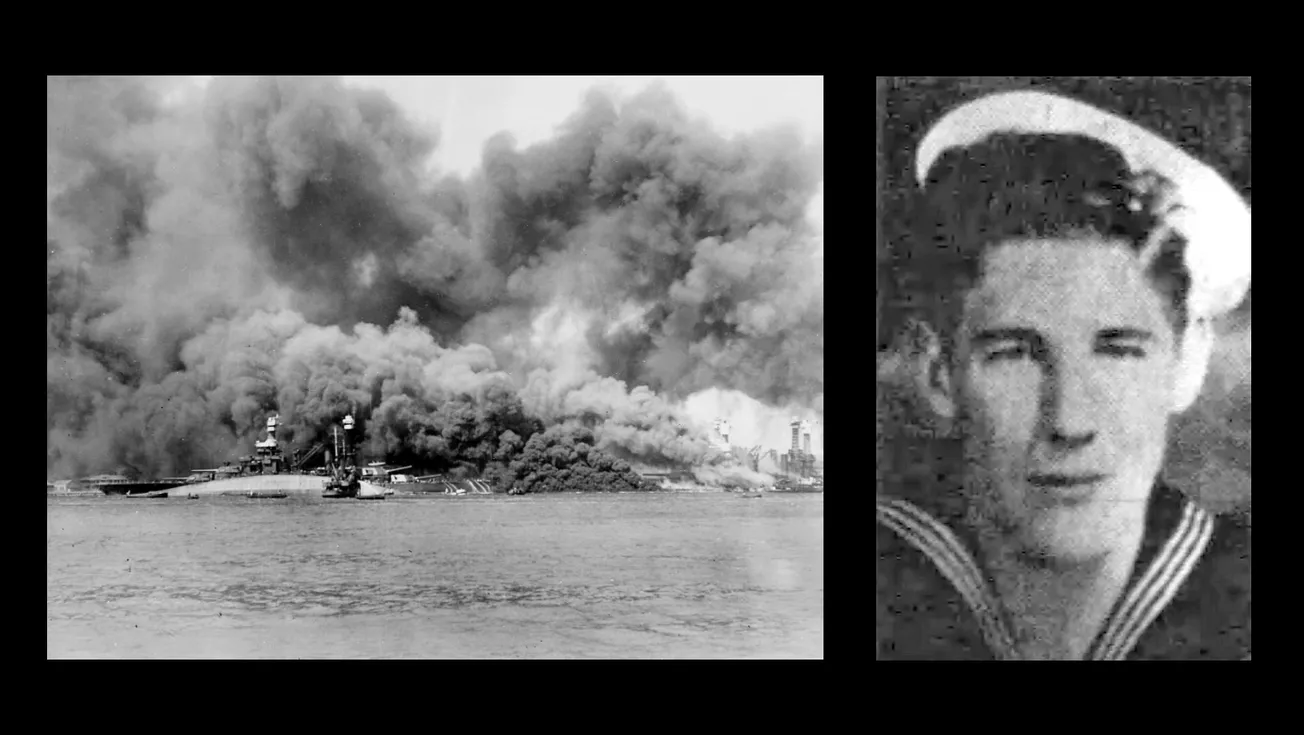

Fireman Second Class Allison, 21, was one of 429 officers, sailors, and marines who died when the battleship the USS Oklahoma was lost in the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, that plunged the U.S. into World War II. Most of their remains, including Allison's, were unidentifiable and were ultimately buried in Honolulu’s National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, popularly known as “the Punchbowl," where their names are recorded in the Courts of the Missing.

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency exhumed their remains for DNA analysis. Allison’s identity was confirmed last October. Several crewmen from Kentucky have been accounted for; nine, including Allison, are in my book, “Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor: Stories from the Day of Infamy” (University Press of Kentucky, 2020)

Allison will be buried next to his parents, Henry Neal and Opal Allison. His identification was especially welcome news to his nieces, Brenda Lowe of Richmond and Pamela Bottoms, who lives in Lone Oak, a Paducah suburb. Both were born after his death, but his DNA matched theirs, a Paducah Sun story said.

The 27,500-ton Oklahoma was one of the largest ships in the Navy. Blasted by aerial torpedoes, it capsized and sank, trapping hundreds of men, apparently including Allison, below decks. Sailors and civilian Navy Yard workers managed to cut through the bottom of the hull and free some men.

Ultimately, the Oklahoma was righted and refloated; the remains of its dead were recovered. The battlewagon was too heavily damaged to return to service, so the Navy decommissioned it and sold it for scrap. The Oklahoma's hulk ingloriously sank in a 1947 storm while being towed to the West Coast.

Allison joined the "Okie" in 1940. He rose through the ranks to fireman second class, but his job was working on the ship’s engines and related machinery, not battling blazes.

His parents evidently knew nothing of the Pearl Harbor attack until the day after it happened. The couple was listening to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Dec. 8 war declaration on the radio. Suddenly, Opal rose from her chair and announced, “My son is dead,” according to a Sun story on Dec. 7, 1991.

On Dec. 21, 1941, the Allisons received a Navy telegram reporting that Hal Jake was missing in action. Devoid of details, such cables left recipients hoping for the best and fearing the worst.

Their worst fears were confirmed on February 12, 1942, when they got another Navy telegram explaining that “AFTER EXHAUSTIVE SEARCH IT HAS BEEN FOUND IMPOSSIBLE TO LOCATE YOUR SON…AND HE HAS THEREFORE BEEN OFFICIALLY DECLARED TO HAVE LOST HIS LIFE IN THE SERVICE OF HIS COUNTRY AS OF DECEMBER SEVENTH NINETEEN FORTY ONE.”

Henry Neal and Opal had received a letter from Hal Jake, which he wrote at sea on December 5. “He indicated that they would probably make port on Saturday and that he would write them again at that time,” the Paducah Sun-Democrat reported on December 22, 1941, in a story about the telegram.

When Allison’s remains were identified, Gov. Andy Beshear said that flags would be lowered to half-staff on the day of the sailor’s reburial in Kentucky. “These identifications are always heartbreaking for the families and for all Kentuckians who honor their service and sacrifice,” he added. “But we are grateful for the scientific advances and professional determination that make it possible finally to bring our heroes home.”

David Heathcott of Mayfield, a docent at the Discovery Park in Union City, Tenn., is also thankful that Allison is finally homeward bound. He treasures an Allison family scrapbook filled with old newspaper clippings about the sailor. He let me use it for my book.

“My own uncle, Harold Gargus, was killed in action by a Japanese Kamikaze in 1944,” Heathcott said. “We knew we would never see him in our lifetime. I greeted the news about Hal with great emotion. Sometimes things come full circle. And it is good.”

--30--

This piece originally ran in the Courier-Journal.