The controversial statues of Confederate Maj. John B. Castleman and nativist Louisville Journal editor George D. Prentice will be gone by the end of the year, according to news reports.

Good riddance.

A special panel named by Mayor Greg Fischer said the monuments “honoring the Confederacy are unwelcome in Louisville and do not represent what the city looks like today, [italics mine].” wrote the Louisville Courier-Journal’s Philip M. Bailey.

In fact, Castleman represented a Louisville that never was during the Civil War either. And Prentice represented a Louisville that was, but shouldn’t have been.

The Castleman statue

Louisville was a Union town …

“Louisville was a Union bastion,” wrote Robert Emmett McDowell in City of Conflict: Louisville in the Civil War 1861-1865. “No later twisting of the facts can change that simple truth.”

He’s right. Louisville roundly rejected disunion. Hundreds more local men marched off to war in Yankee blue than in rebel gray.

And what of those who chose rebel gray? “The principal legacy of a Confederate soldier in the American Civil War cannot be whitewashed,” editor Aaron Yarmuth wrote in LEO Weekly. “He was unquestionably a traitor to his country.”

He’s right, and a hefty majority of Louisvillians would have agreed during America’s most lethal conflict. Prentice penned editorials that suggested rebels should he hanged. The Journal was Kentucky’s leading unionist paper.

… but not an abolitionist town

“As a Confederate officer, [Castleman’s]…principal legacy is that of fighting for the oppression and enslavement of African-Americans,” Yarmuth added.

Right again. But Louisville’s (and Kentucky’s) unionism did not include opposition to slavery. Most Kentuckians were pro-Union and pro-slavery, like the Journal.

In the presidential election of 1860, Kentucky native Abraham Lincoln, the anti-slavery Republican, managed just 1,364 votes in slave state Kentucky—106 in Louisville. (Jefferson County went for pro-Union and pro-slavery John Bell, the conservative Constitutional Unionist.)

In 1864, Kentucky gave Democrat (and less-than-stellar Yankee general) George B. McClellan almost 70 percent of its vote. In no other state did the Great Emancipator fare so poorly at the polls, according to Presidential Politics in Kentucky 1824-1948 by Jasper B. Shannon and Ruth McQuown.

Most of Kentucky was Union, not Confederate

Nonetheless, in the secession crisis of 1860-1861, Louisville and almost everywhere else in Kentucky—except the Jackson Purchase, the state’s only rebel-majority region—came down squarely on the Union side.

The Kentucky Union Party was born in Louisville in January, 1861. A Union rally at the old Jefferson County courthouse on Washington’s birthday—Feb. 22—drew thousands. Prentice helped hoist a huge American flag over the roof of the historic structure that still stands.

In the state legislature, Louisville and Jefferson County lawmakers helped lead the Union majority that thwarted the secessionist minority at every turn.

Louisville went solidly Union in the elections for a new state legislature in August. When Union and Confederate forces invaded the state in the Purchase in September, 1861, Louisville legislators helped turn Kentucky away from its fragile neutrality—officially established a month after the war started in April—and toward outright support for fighting on the Union side.

Louisville warmly welcomed the Yankee troops. In The Civil War and Readjustment in Kentucky, E. Merton Coulter included a unionist’s account of the advent of Yankee troops in Louisville: “The regiments that pass through here are unanimous in declaring that they have had a reception in Kentucky so far beyond anything they have found elsewhere, that they scarcely know what to do with themselves in the pressure of the glowing hearts and liberal hands that shower upon them substantial comforts and blessings.”

It is true that Kentucky’s unionist ardor waned after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1862, though it didn’t apply to the state. Nearly all unionists were as racist as their rebel foes.

Nonetheless, to the war’s end in 1865, as many as 90-100,000 Kentuckians—white and African American—fought for the Union. Between 25,000 to 40,000 whites soldiered for the South, according to A New History of Kentucky by Lowell H. Harrison and James C. Klotter.

Why a Castleman statue, then?

The Castleman equestrian statue in Cherokee Triangle, like the large Confederate monument that was hauled away from near the University of Louisville campus, has more to do with how Louisvillians came to view the war than with the war itself.

Kentucky embraced the Confederacy only after it was defeated, historian Anne E. Marshall explained in her book, Creating A Confederate Kentucky: The Lost Cause and Civil War Memory in a Border State.

“In a postwar world where racial boundaries were in flux, the Lost Cause and the conservative politics that went with it seemed not only a comforting reminder of a past free of nineteenth century insecurities but also a way to reinforce contemporary efforts to maintain white supremacy,” wrote the Lexington native, who’s a history professor at Mississippi State University.

Confederate statues and memorials in border state Kentucky and the South are ugly relics of American apartheid—the Jim Crow era, when segregation and race discrimination were entrenched in law and the social order.

Castleman lived to 1918 and was among the white supremacist powers-that-be who ran Louisville. Per his instructions, his coffin was draped with American and Confederate flags, according to Bailey’s story.

In his memoirs, published in 1917, Castleman fondly recalled his rebel army days and slavery. Among masters and slaves, “the interests were mutual, and almost always contentment and happiness prevailed,” he wrote.

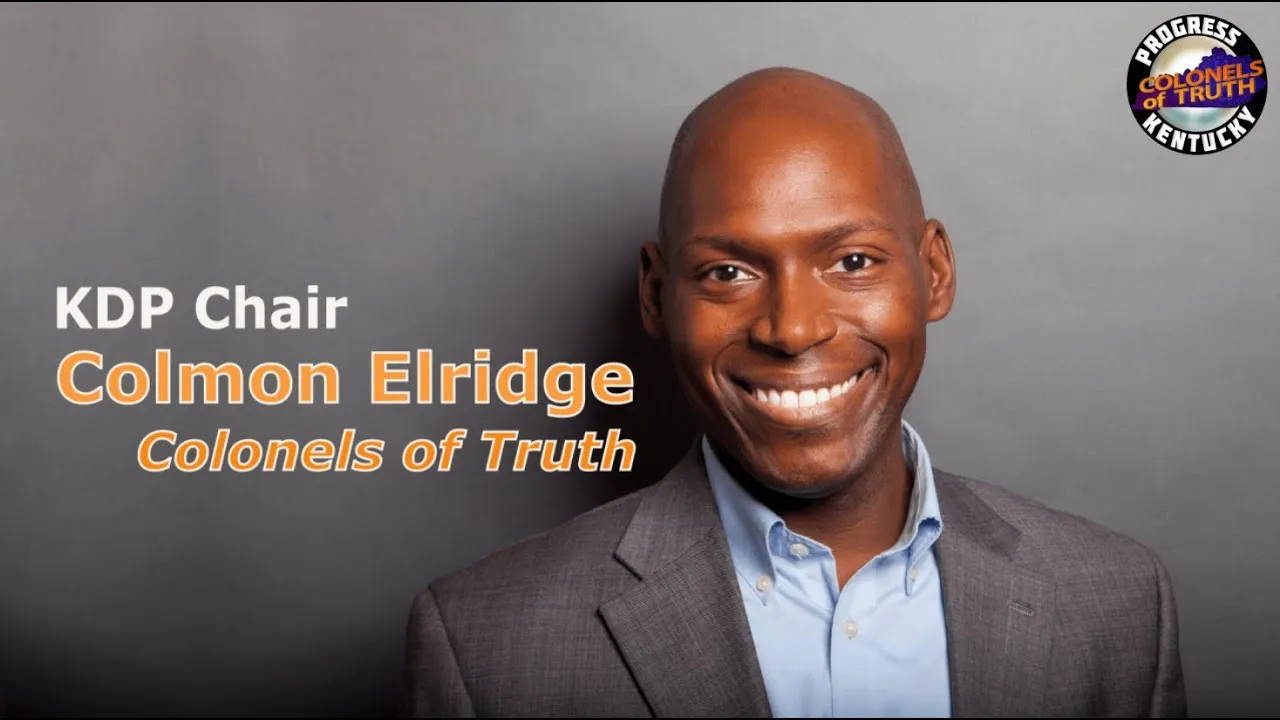

The Prentice statue

Prentice: pro-union, but also pro-slavery and viciously nativistic

As noted above, Prentice thought anyone volunteering for the Confederacy was a rebel against his country, and deserved to be hung. And, he took part in the Union rally that helped start the Union party.

But he was also pro-slavery, and like most Kentucky whites, was outraged when Uncle Sam started making soldiers of slaves.

Prentice, who got behind Bell in 1860, had never backed a Democrat for president. He was so angry over Lincoln’s policies that the Journal endorsed Lincoln’s opponent, McClellan.

Before the war, Prentice supported the anti-Catholic and anti-foreign American or Know-Nothing Party. His viciously nativist editorials preceded “Bloody Monday,” the notorious Aug. 6, 1855, election day riot when Protestant, native-born mobs rampaged through German and Irish Catholic neighborhoods in Louisville, shooting, burning, and looting.

Close to two dozen people died, some of them naturalized citizens on the way to the polls. Scores of immigrant homes and businesses were destroyed.

Louisville’s Know-Nothing mayor condemned the mobs. Ultimately, the party faded away in Kentucky and nationally.

Prentice’s death and his statue

After the war, Prentice remained editor of the paper, which in 1868 merged with the Louisville Courier and the Louisville Democrat to become the Courier-Journal. Two years later, Prentice died of influenza and was buried in Cave Hill Cemetary.

In 1875, a statue of Prentice was completed and dedicated in front of the Courier-Journal building, but was moved in 1914 to the public library’s main branch. Through the years, it has become more and more controversial, as Prentice’s anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant views and writings have become better known.

The fate of the statues

The likenesses of Prentice and Castleman—and all Confederate monuments—should be removed. Wherever possible, they should go into museums where they can be explained and placed in historical perspective.

In any event, they should not be remain objects of veneration in public places.

In his story, Bailey quoted Mayor Fischer: “Moving the…statues does not erase history. It allows us to examine our history in a new context that more accurately reflects the reality of the day, a time when the moral deprivation of slavery is clear.”

The notion of slavery as a “moral deprivation” was lost on Castleman, Prentice, and most white Kentuckians during the Civil War and afterwards. If the likenesses of Castleman and Prentice wind up in museums, I hope curators will leave the graffiti and paint smears on them to reflect modern-day Louisvillians who indeed clearly see the immorality of the Confederacy, slavery, racism, and nativism.

–30–

Castleman Statue: Photo taken by w.marsh on 2/27/06 [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons.

Prentice Statue: GNU Free Documentation License at Wikipedia.