Another Kentucky sailor is coming home nearly 82 years after his life ended on the day President Franklin D. Roosevelt said would “live in infamy.”

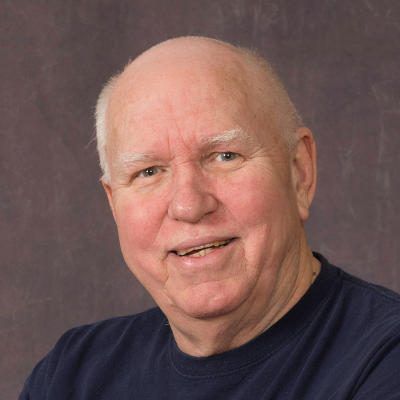

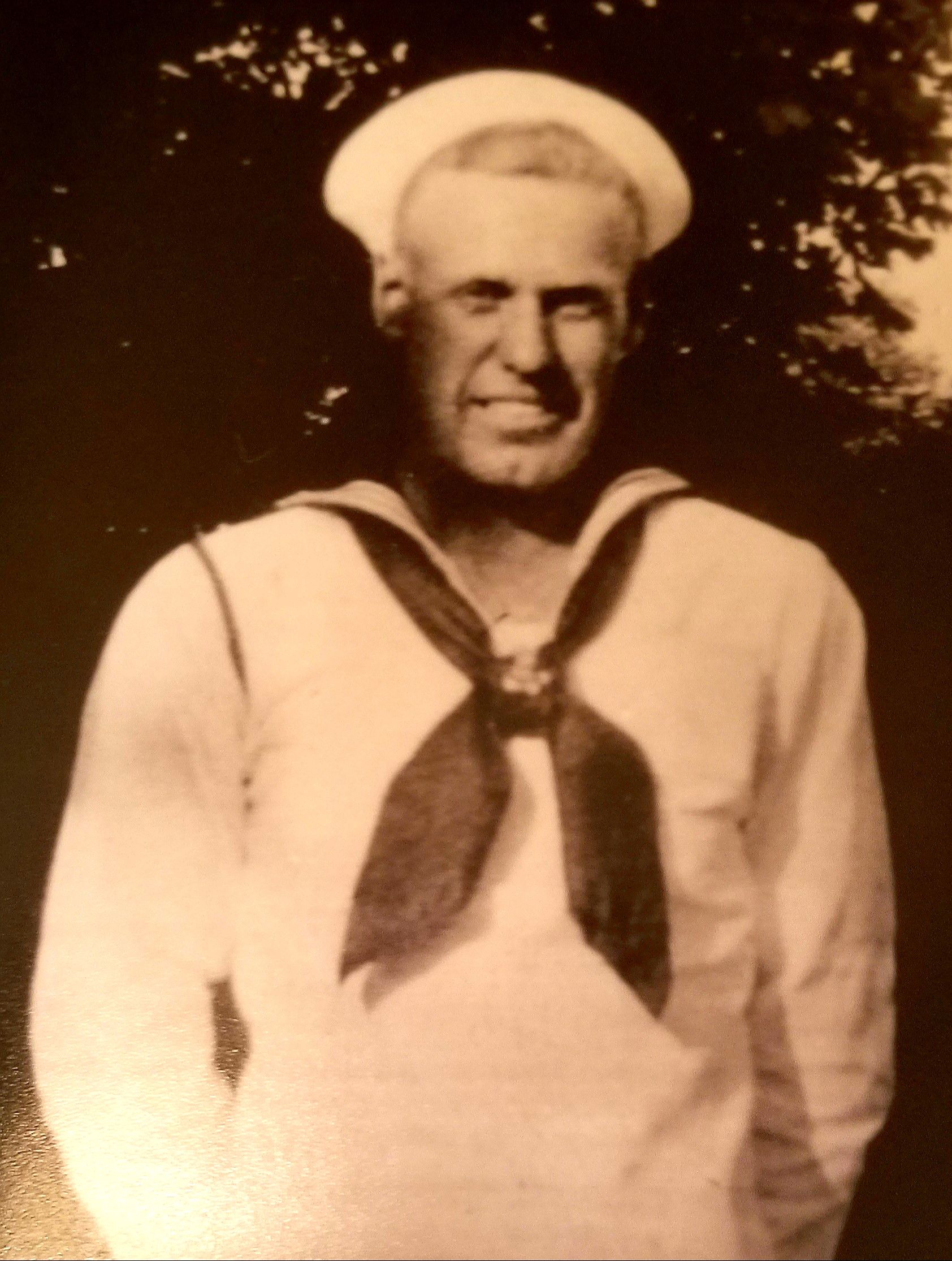

Gov. Andy Beshear's communications office issued a press release announcing that the remains of Navy Seaman First Class Elmer P. Lawrence of Park City will be reburied in Shiloh Baptist Church Cemetery in Railton on July 22 following funeral services at the Barren County house of worship.

Lawrence, 25, was among 429 USS Oklahoma crewmen who perished on Dec. 7, 1941, during the devastating Japanese surprise air raid on the big Navy base at Pearl Harbor, and Army and Marine air bases elsewhere on Oahu. The attack sent the U.S. into World War II.

The torpedoed Okie capsized and sank in the air raid that killed more than 2,400 Americans, including 68 civilians.

“We are saddened to acknowledge the death of another young Kentuckian who died in the attack on Pearl Harbor,” the release quoted the governor. “But we are gratified that modern science and military determination has, against all odds, found him and will bring him home.”

Two years ago, Lawrence’s remains were identified by scientists from the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency and the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System. They used “dental and anthropological analysis” and “mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and autosomal DNA (auSTR) analysis,” according to the release.

The unidentifiable remains of Lawrence and 393 of his shipmates — sailors and Marines — were ultimately transferred from other cemeteries to Honolulu’s sprawling National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, dubbed “the Punchbowl” because it is in the caldera of an extinct volcano.

The names of more than 13,000 World War II soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines are recorded on marble monuments in the cemetery’s ten Courts of the Missing.

A bronze rosette, which denotes a veteran has been “accounted for,” will be placed next to Lawrence’s name, if one hasn’t been already.

“Between June and November 2015, Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) personnel exhumed the USS Oklahoma Unknowns from the Punchbowl for analysis,” the release says.

Eight torpedoes dropped from low-flying torpedo bombers slammed into the 27,500-ton Oklahoma’s port side, blasting gaping holes in the hull. A ninth one finished off the doomed ship, which terrifyingly had rolled on its side, capsized, and sank in the harbor mud. (All told, Japanese pilots, flying off six aircraft carriers, sunk or significantly damaged 21 ships.)

Sailors and civilian Navy Yard workers managed to cut open the bottom of the Oklahoma and free several men trapped inside. The dead remained entombed in the stricken warship until the Navy began a massive salvage operation in 1943.

Amazingly, work crews managed to turn the Oklahoma upright, patch the hull and refloat the battlewagon. Crew remains were also recovered.

Once righted, the Okie was placed in drydock to be stripped of guns and other usable equipment and patched sufficiently to make it relatively watertight.

But the Navy decided that the 1916-vintage capital ship was too outmoded and too heavily damaged to return to service. So it was decommissioned in 1944 and sold for scrap in December, 1946. In May, 1947, the Oklahoma ingloriously sank under tow from Pearl Harbor to California.

I don’t know if Lawrence knew Machinist’s Mate First Class Ulis Claude Steely of Corbin, another Kentucky sailor on the Oklahoma whose remains were identified and, in 2019, brought home. Steely, who was killed at age 25, is in my book, Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor: Stories from the Day of Infamy, which the University Press of Kentucky published in 2020.

I included a famous quote from the late Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler, who was a Kentucky governor and U.S. senator: “I never met a Kentuckian who wasn’t either thinking about going home or actually going home.”

Steely came home in a shiny, silver-colored casket that was flown from Honolulu to Atlanta and on to Lexington. A hearse took him the rest of the way to Corbin. He was buried with military honors in the cemetery at Grace on the Hill Church, where his father pastored.

I also quoted Corbin Mayor Suzie Razmus who told a Louisville Courier-Journal reporter: “The feelings that the country have for the greatest generation is felt very strongly everywhere obviously. But we’re a rural community. Family is everything to us. Home is everything to us.”

Doubtless, family is also everything to the descendants of Seaman Lawrence, whose long journey back to Kentucky is almost over.

--30--

| Tip Jars |