There’s a picture that apparently exists in the minds of the majority of Kentucky lawmakers.

It’s a picture of a law enforcement agency’s harried records custodian recklessly and without reference to the law — much less public safety — releasing banker’s boxes of investigative records to morbidly curious open records requesters or requesters with bad intent.

That picture is entirely false.

The reverse of that picture is of a law enforcement agency’s uncooperative records custodian jealously withholding banker’s boxes of investigative records — without reference to the law and underlying facts — from media requesters, concerned citizens or aggrieved family members of victims (and even perpetrators) searching for answers. It, too, is false.

The truth lies somewhere in between. In most cases, however, it is closer to the second picture than the first.

A culture of secrecy is embedded in law enforcement, and records custodians tend to err on the side of nondisclosure.

For decades, law enforcement has, with the blessing of Kentucky’s attorneys general past and present, summarily denied access to investigative records in open criminal investigations by simply noting that fact in boilerplate responses. They rarely reviewed the requested records to separate exempt from nonexempt information (and release the latter) as required of all other public agencies.

Law enforcement treated an investigative file as a single record. That record was exempt because the underlying investigation was open.

Rest assured, there are no cases in Kentucky in which a records custodian has inadvertently disclosed a record that identified an informant (statutorily excluded from access since the law’s enactment); a witness (“categorically” excluded from access under the Supreme Court’s holding in Kentucky New Era v. City of Hopkinsville); or an undercover police officer in responding to an open records request.

Last year’s Kentucky Supreme Court ruling in Shively Police Department v. Courier Journal threatened law enforcement’s comfortable, but legally unsupportable, “status quo.” By rejecting a much-used alternative argument under a separate statute — which was believed to require no showing of harm while an investigation was open — and affirming a 2013 case recognizing that harm was not presumed from the “open” status of the case, law enforcement found itself in the same position as every other public agency that denies access — forced to meet its burden of proof to sustain denial of an open records request on a case by case basis.

That is when lobbyists and law enforcement sprang into action, urging lawmakers to pass a bill that would reverse the damage and restore law enforcement’s comfortable “status quo.” That is when “would” became “could” and actual harm became merely possible harm.

The committee hearings and floor debates on House Bill 520 exposed such a fundamental misunderstanding of the law enforcement exception to the open records law that we must assume picture No. 1 floats in the minds of a substantial number of uninformed lawmakers who were vulnerable to law enforcement’s and lobbyists’ false narratives.

Let’s correct these false narratives. We can, without fear of successful repudiation, assure Kentuckians:

- If an investigation, such as the drug investigation Rep. Chris Fugate (R-Chavies) described, is conducted by more than one law enforcement agency (either another state’s or federal), investigative records in Kentucky’s possession need not be released to a requester, even if Kentucky’s investigation is concluded.

Kentucky agencies can rely on the law enforcement exception at the request of, and on behalf of, another state or the FBI if those agencies’ investigations remain open and they confirm that Kentucky should withhold the records and why. Thus, numerous open records decisions by numerous attorneys general recognize:

“Where there is concurrent jurisdiction between two agencies, and they both have an interest in the matter being investigated, the records of one agency may be withheld, under authority of KRS 61.878(1)[(h),] if premature release of the requested records would harm the ongoing investigation and prospective law enforcement action of the other agency.”

- The law enforcement exception has rarely been amended during its long history. In the early 1990s lawmakers added a permanent exclusion for commonwealth and county attorneys’ criminal litigation files. The exception was also re-numbered as other exceptions were added to KRS 61.878(1). One proposed change from this year’s Senate committee substitute was irresponsibly, and some would say shamelessly, added. By clear and thoughtful design, the attorney general’s criminal litigation files were not given permanent protection from public inspection by past legislatures as commonwealth and county attorneys’ were. There are critical but nuanced reasons for this dichotomy which I am happy to discuss if the sponsor of the Senate committee sub cares to understand.

- Supporters of the bill who testified at the Senate State and Local Government Committee implied that lawmakers’ concerns should be assuaged by the final sentence in HB 520. The law enforcement exception has always concluded with this sentence, “The exemptions provided by this subsection shall not be used by the custodian of the records to delay or impede the exercise of rights granted by KRS 61.870 to 61.884[.]” That language is nothing new.

That dog won’t hunt.

- No doubt, some investigations may be open for a short duration. It was surprising to learn from Rep. Fugate that a year to 18 months is the norm for multistate drug investigations. In my experience as an assistant attorney general reviewing open records appeals over 25 years, many cases, if not most cases, remain open over a significantly longer period of time. Some are deemed open for decades (even if inactive) — in one extreme case, for 25 years, and another, in excess of 40 years.

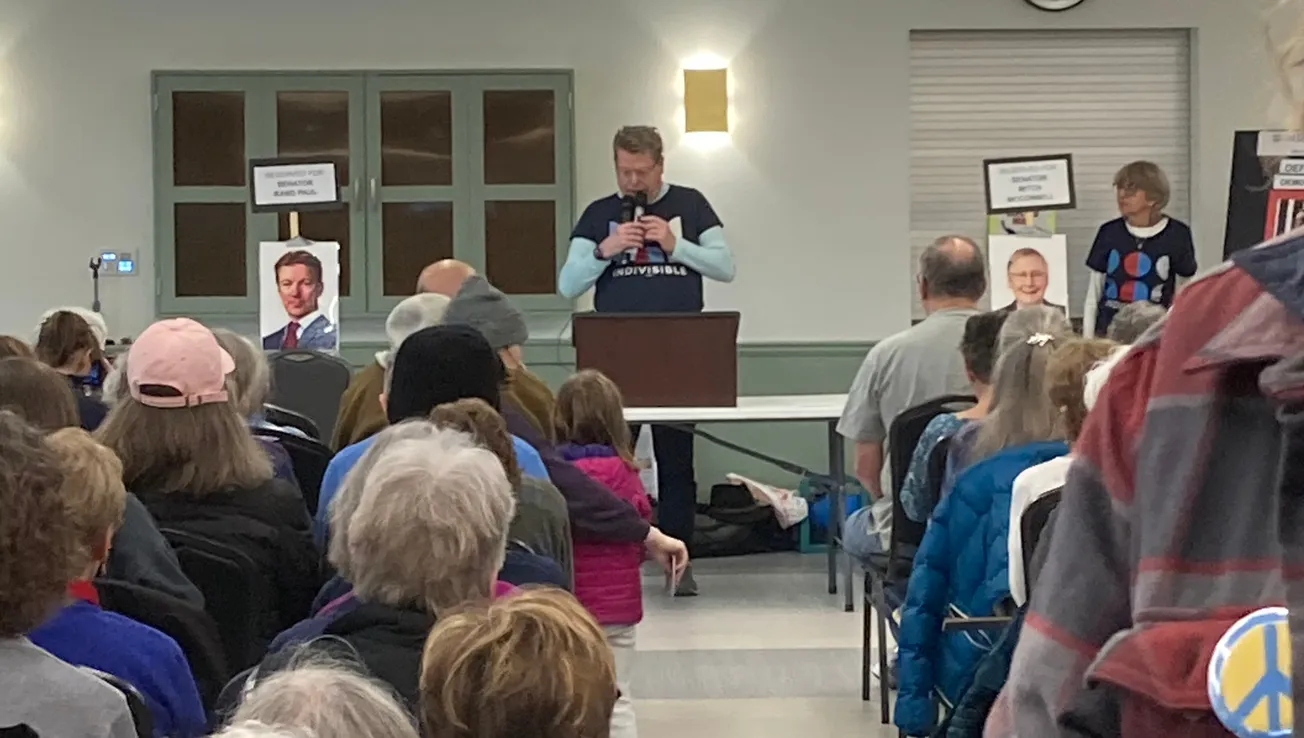

- Elected state representatives who live in glass houses should not throw stones. A March 15 Middletown Town Hall featured comments from one such legislator that were both misleading and bullying. The remarks targeted unnamed open government advocacy groups and individual advocates for “saying words that sound really damning” unless you know the facts.

In the cynical belief that no one knew the law as well as he, the representative proceeded to extoll the virtues of HB 520 because it authorizes nondisclosure of investigative records of a law enforcement agency, while the investigation is open, if the agency can articulate “the reasons” for denial. It is also worthy of support, he argued, because it empowers a requester dissatisfied with a law enforcement agency’s denial of a request to appeal that denial to the Attorney General.

Anyone who knows anything about the Kentucky Open Records Act knows that the law has afforded these protections to the agency and to the public for decades. No open government advocate opposed HB 520 on these grounds.

It was the dilution of the harm requirement — substituting “could” for “would” in a way that lends itself to the long rejected presumption of harm simply because a case is open — to which we objected.

Perhaps the representative should consider if it isn’t he who is “saying words that sound really damning” to stir up support for a bill that, in the final analysis, is likely to do more harm than good to the public’s right to know.

Whether it will, and what that harm will look like, only time will tell.

--30--