It’s a pretty safe bet that between now and Tuesday, First District U.S. Rep. James Comer won’t bite one constituent’s thumb off, or duke it out with another.

That’s ditto for Comer’s challenger, Jimmy Ausbrooks.

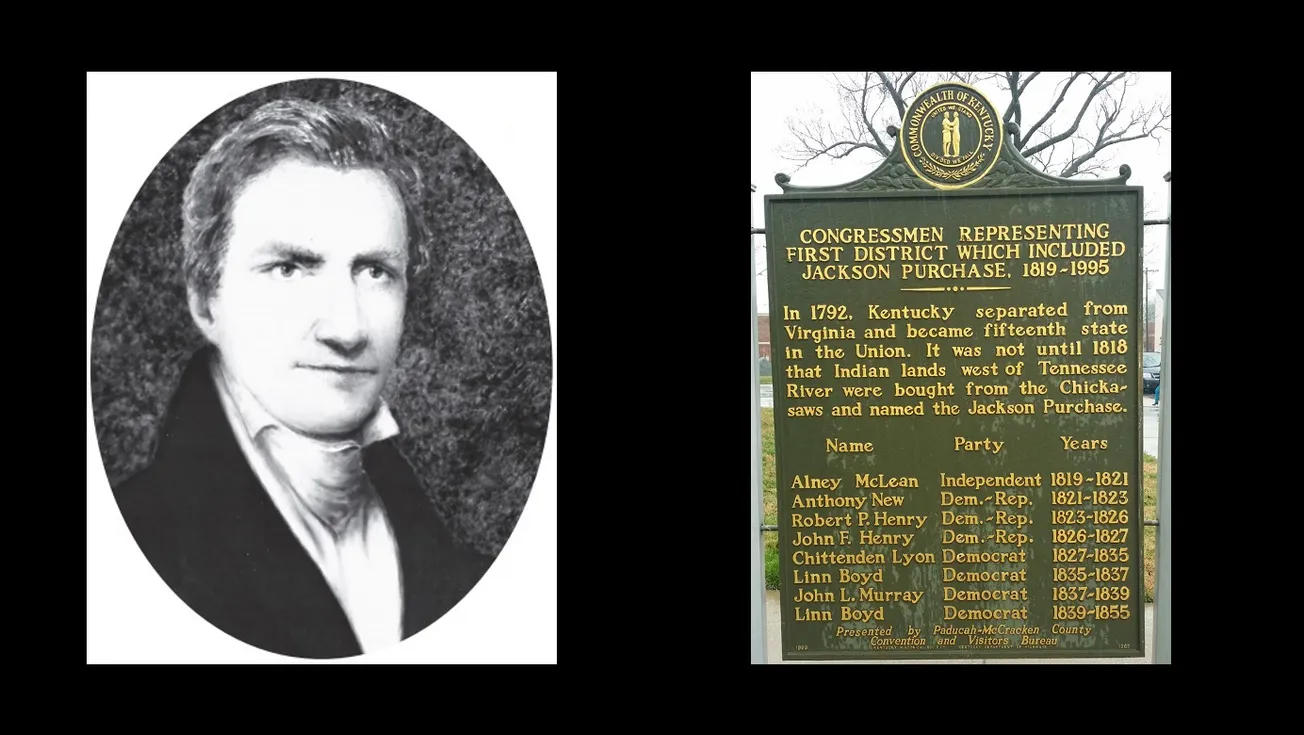

Even so, there would be precedent. Former First District Congressman Matthew Lyon used his teeth to amputate his assailant’s first digit. It was self-defense.

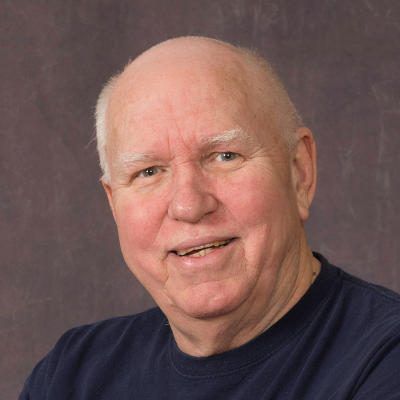

Chittenden Lyon, who later followed his father to Congress, brawled with a bruiser. After all, he wanted the guy’s vote.

Irish-born Revolutionary War veteran Matthew Lyon, who'd been a Vermont congressman, moved to frontier western Kentucky and helped found Eddyville on the Cumberland River. Popular and prosperous, he was elected to Congress in 1803 and stayed until 1811. (Eddyville is the seat of Lyon County, which was named for Chittenden Lyon.)

A staunch Jeffersonian Republican, Lyon said he enjoyed continued political success by strategically positioning himself “at a crossroads by which everybody in the district passed from time to time … abusing the sitting member,” according to Henry Clay: Spokesman of the New West by Bernard Mayo.

On one occasion, abuse came from an unhappy voter named Cofield, who dredged up the old story about Lyon spitting in the face of Congressman Roger Griswold, a Federalist foe. (A year later, Lyon was briefly jailed under the Alien and Sedition Acts for printing commentary sharply critical of President John Adams in “The Scourge Of Aristocracy and Repository of Important Political Truth,” the congressman’s newspaper.)

While Lyon continued to excoriate Adams from behind bars, his constituents reelected him. After he was released, he returned to Congress and cast Vermont's vote for Thomas Jefferson for president. Jefferson and Aaron Burr were knotted in the electoral college in the presidential election of 1800, in which Adams had sought a second term.

About two weeks after Lyon’s great expectoration, he and Griswold came to blows on the House floor; the latter was armed with a hickory walking cane and Lyon with tongs he snatched from a fireplace.

Neither combatant was seriously hurt, but Griswold knocked Lyon flat. So did Cofield, who pinned Lyon to the ground in preparation for delivering the coup de grace in a backwoods brawl: popping out an eyeball with a thumb flick.

But when Cofield shoved his thumb toward Lyon’s face, the lawmaker managed to get the digit in his mouth and sever it at the first joint, according to Mayo.

In 1822, the “The Spitting Lyon” moved west again and died in Arkansas at age 73. Chittenden saw to his father’s burial in old Eddyville’s Riverview Cemetery. (Most of the town was moved inland with the completion of Barkley Dam and the creation of Lake Barkley.) In 1827, Chittenden won his parent’s old seat in Congress and held it until 1835.

The Lyon cub was “a man of prodigious physical proportions, being 6 1/2 feet height in his stockings, and weighing 350 pounds,” according to Lewis and Richard Collins’s 1874 History of Kentucky.

Like his famous father, he relished a political fight, even if it involved fisticuffs. So he accepted a challenge from Andy Duncan “to go out on fair ground, and fight him a fair old-fashioned Kentucky fist fight,” the history book says.

Duncan “was bitterly opposed” to Lyon.” He was also “a man of like powerful frame and strength, and nearly as large, and nearly [Lyon’s] … equal in personal prowess.”

The book isn’t clear whether the slugfest happened when Lyon was running for the state Senate or Congress. But “at it they went – Duncan quite confident that he could give the colonel a good trouncing.”

Explained the father and son historians: “The fight was long and bloody, and neither showed signs of relinquishing the field or even whispering ‘hold, enough.’ At last, friends parted them and called it a drawn battle.”

After washing up, Lyon and Duncan enjoyed “a drink together of Old Robertson whisky (of which they were both fond), shook hands, and made friends for the occasion. … Duncan kept his part of the contract, and gave a hearty vote for his jolly competitor in the square stand-up fight.”

Lyon was 55 when he died in 1842. He was interred near his father. The legislature carved Lyon County from Caldwell County in 1854.

Mayo said by chomping off Cofield’s thumb, Lyon helped confirm eastern opinions “that Kentucky was truly a paradise for barbarous Yahoos.” It seems likely that Lyon’s offspring provided more proof.

At any rate, the Spitting Lyon proved himself a master of the sound bite.

--30--

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story is based on material in Craig's book, True Tales of Old-Time Kentucky Politics: Bombast, Bourbon and Burgoo.