Donald Trump keeps saying he’s the champion of forgotten “real Americans,” mostly meaning conservative white folks, notably those in rural America.

Millions of rural whites keep believing him. He feeds their anger and resentment at what they see as their loss of “real American” status in an America that’s growing more urban and diverse and less rural and white.

But rural whites are the most powerful large demographic in the country, Tom Schaller and Paul Waldman argue convincingly in White Rural Rage: The Threat to American Democracy. Schaller is a political scientist, researcher, and author at the University of Maryland-Baltimore. Waldman is a journalist, opinion writer and author who was a Washington Post columnist.

Not only is white rural rage misplaced, it is imperiling the republic, according to the authors. While rural whites represent 15 percent of the population, they enjoy political clout far greater than their numbers in Washington and in state capitals like Frankfort.

|

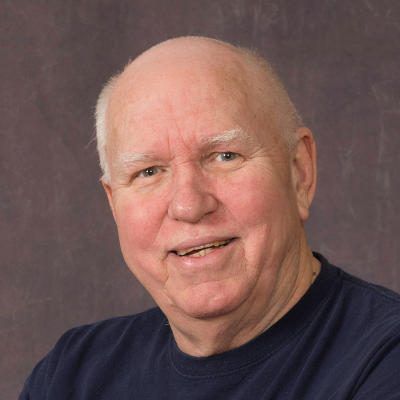

I’m a white guy who has lived in conservative, rural, and largely white western Kentucky all my 74 years. White Rural Rage would be about as popular as a wet dog at a wedding in my neck of the Bluegrass State woods. From the pulpits of white, evangelical churches it might even be condemned as Satan’s scribblings.

But the Good Book says “the truth will set you free.” Schaller and Waldman have employed an impressive array of evidence, including polls and studies, to write a book that tells a hard truth that needed telling, and not just in parts of the county like mine where most people can’t wait for a Trump Second Coming. (You’ve probably guessed that I’m not one of them.)

Nowhere else is Trump more adored than in rural white America, “a landscape of political emptiness in which a lack of real competition leaves Democrats believing there’s no point in trying to win rural votes and Republicans knowing they can win those votes without even trying – and give the people who supply them nothing in return,” wrote Schaller and Waldman.

Rural whites claim they are overlooked by Uncle Sam — except by Trump and MAGA politicians — and belittled in the “lamestream media.”

Since Trump’s advent, few demographics “have received more fawning attention from hand-wringing journalists and pundits than rural Americans, especially disgruntled rural White voters,” Schaller and Waldman wrote.

Simultaneously, “political observers began openly fretting over the fate and even the survival of American democracy,” yet “almost nobody has noticed that these two phenomena are connected,” the authors added.

Though rural whites claim “often, but not always, with cause” that government neglects them, “hundreds of state and federal programs” are there to help them. Too, their outsized political might enables them to use “unusual leverage to bend politics and politicians to their will.”

At the same time, politicians and pundits constantly venerate “rural White culture and values as somehow superior to those of almost every other group of Americans.” But, the authors warn, “the mythic status conferred upon rural citizens – and rural Whites especially” gives them greater latitude to embrace anti-democratic behavior.

The hard-right Republican politicians white rural voters elect fob them off with “culture war trinkets” instead of addressing “in more substantive ways the economic and health-related maladies crippling so many small, sparsely-populated towns and counties – thereby perpetuating the cycle of despair.” Schaller and Waldman admit they’re puzzled by “this willingness to trade away a substantive agenda of local improvement in favor of nursing cultural grievances.”

When Trump hit the campaign trail in 2016, he promised to “Make America Great Again.” He meant for white folks to hear “Make America White Again.” Millions did and voted accordingly. Running for vice president 56 years before, Lyndon B. Johnson, a rural Texan who understood the roiling racism of his state and the rest of rural Dixie (not coincidentally, the MAGA heartland) declared: “If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.”

In short, Schaller and Waldman wrote that rural Whites are being “manipulated by the selfish motives of skilled authoritarians like Trump and a growing legion of copycats” who “now pose a rising threat to the state and fate of American democracy.”

But here’s the part of the book that I suspect would turn white rural rage white hot: where Schaller and Waldman wrote that rural white people as a group are “uniquely hostile toward racial and religious minorities, recent immigrants, and urban residents generally,” that rural whites are most likely to be election deniers and birthers, and that they are most apt to believe “unhinged QAnon claims.”

At the same time, rural whites are the demographic most skeptical of science, and are the people least likely to support fundamental principles of American democracy such as separation of powers, checks and balances, voting rights, federalism, and a free press. According to Schaller and Waldman, rural whites are more prone toward going along with authoritarianism, more police power, and more restrictions on immigration. They “express greater support for White nationalist and White Christian nationalist movements.” Too, no other demographic shows “a higher degree of support for, or justification of, violence as an appropriate means of public expression and decision making” than rural Whites.

The authors also showed that the Senate tilts toward rural white America. The 49 Democrats and the three independents who caucus with them represent nearly 193 million Americans. The 49 Republicans, nearly all of them from states with significant rural populations, represent fewer than 140 million.

The outsized political advantage of rural whites is also reflected in how we elect presidents – by the Electoral college and not by popular vote.

Schaller and Waldman point out that Trump lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton in 2016 but won where it counted – in the Electoral College. Trump (in 2016) and Biden (in 2020) each won 306 electors, but only in Biden’s victory did the electoral vote and popular vote align.

Schaller and Waldman explain how Republican majorities gerrymander state houses and congressional districts to benefit pro-GOP rural white counties over multiracial cities that lean Democratic. “The GOP systematically maximizes the electoral power of rural areas at the expense of urban areas,” they write.

There’s no better example than the Kentucky General Assembly.

Schaller and Waldman concluded that the lack of a unified political movement with a clearly stated agenda is a big reason rural America is so easily bilked by self-serving politicians. The authors proposed that the first step toward organizing a powerful movement requires rural whites to admit “that they’ve been blaming the wrong people for their problems. What we said at the outset of this book bears repeating: Hollywood didn’t kill the family farm and send manufacturing jobs overseas. College professors didn’t pour mountains of opioids into rural communities. Immigrants didn’t shutter rural hospitals and let rural infrastructure decay. The outsiders and liberals at whom so many rural Whites point their anger are not the ones who have held them back.”

White Rural Rage makes it plain that it’s the very politicians angry rural whites elect who are holding them back. “So what do rural Whites get in return for all they bestow on the GOP?” Schaller and Waldman asked, also early in the book, then answered, “Almost nothing. The benefits they receive are nearly all emotional, not material. They’re flattered and praised, and then they get whatever satisfaction can be had from watching their party win office and their enemies despair.”

Not surprisingly, the book has multiple detractors, including some liberals. The naysayers remind me of former TVA Chairman Gordon Clapp’s oft-quoted observation: “TVA is controversial because it is consequential; let it become insignificant to the public interest, an agency of no particular account, and people will stop arguing about it.” That’s also true of books like White Rural Rage.

Critics include Nicholas F. Jacobs, a Colby College political scientist, researcher, and author. In a Politico article, he blasted the book, charging that the authors got the data wrong, including some of his research.

“I’m an academic who studies rural Americans and lives in rural Maine,” he wrote. “My job and passion is to pore over reams of data, including some of the largest surveys of rural voters ever conducted. Sitting on my computer are detailed responses from over 25,000 rural voters that I have conducted over the last decade and used to publish a range of peer-reviewed and widely cited research. And I’ve done it all largely to make sense of why rural voters are continually drawn to the Republican Party.

“But the thing about rage — I’ve never found it.” Never?

I’d be glad to show Jacobs around my corner of Kentucky where a lot of folks pack heat and Three Percenter and Confederate flags fly, often in tandem with Trump flags. There are also the “Let’s Go Brandon” tee shirts and bumper stickers and the “F--k Joe Biden” graffiti.

I emailed Schaller seeking a response to Jacob’s criticism. He replied with a paragraph he said is to be published in The New Republic: Our critics say we misrepresent their work. We do not; we merely assembled in one place a composite picture of rural whites as the most revanchist geodemographic group in America. Our critics want to believe — and worse, want others to believe — that the opinions of the most devout followers of Trump and his racist, xenophobic, undemocratic, and violence-inducing behaviors are somehow mainstream, despite a large and mounting body of evidence to the contrary.

Anyway, nowhere in their book do Schaller and Waldman write, or imply, that all rural whites are bigots, or that cities and suburbs are naturally bigot-free zones. Nor are they the first to warn that white rural Americans are faulting the wrong people for their misery.

“Anger is roiling in Republican America, along with conspiratorial fabrications about who to blame for their condition,” wrote Mike Males, a native of Antlers, Okla. (population about 2,200), in yes! magazine two years ago. “The right-wing canard that hardworking White people subsidize welfare-grubbing cities is backward.”

“Never before have so few with so much, promised to take away so much from so many, and then laugh their asses off as the so many with so little vote for the so few with so much,” Jim Pence of Glendale, Ky. (population about 2,200) posted in every edition of his Hillbilly Report blog.

It’s not, and never has been, “liberal elitists” like Schaller, Waldman, and the Democrats who are shafting — and you can bet, privately poking fun at — rural white Americans. It’s the guy they all but deify and his party. White Rural Rage is a wakeup call for white rural Americans to focus their ire on who and what party is really putting it to them – and start voting accordingly.

--30--

Comments